Angela

Elite member

- Messages

- 21,823

- Reaction score

- 12,329

- Points

- 113

- Ethnic group

- Italian

This time it's in Europe, not Central Asia.

See:

http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/12/15/094243

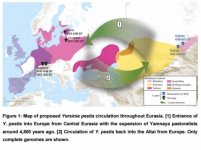

"Molecular signatures of Yersinia pestis were recently identified in prehistoric Eurasian individuals, thus suggesting Y. pestis might have caused some form of plague in humans prior to the first historically documented pandemic. Here, we present four new Y. pestis genomes from the European Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (LNBA) dating from 4,500 to 3,700 BP. We show that all currently investigated LNBA strains form a single genetic clade in the Y. pestis phylogeny that appears to be extinct today. Interpreting our data within the context of recent ancient human genomic evidence, which suggests an increase in human mobility during the LNBA, we propose a possible scenario for the spread of Y. pestis during the LNBA: Y. pestis may have entered Europe from Central Eurasia during an expansion of steppe pastoralists, possibly persisted within Europe until the mid Bronze Age, and moved back towards Central Eurasia in subsequent human population movements."

"it is assumed that plague affected human populations in three pandemic waves. The first, the Plague of Justinian,starting in the 6th century AD, was followed by multiple epidemic outbreaks in Europe and theMediterranean basin, and has been associated with the weakening and decay of the Byzantineempire (Russell, 1968). The second plague pandemic first struck in the 14th century with theinfamous ‘Black Death’ (1347-1352), which again spread from Asia to Europe seemingly alongboth land and maritime routes (Zietz and Dunkelberg, 2004). It is estimated that this initialonslaught killed 50% of the European population (Benedictow, 2004). It was followed byoutbreaks of varying intensity that lasted until the late eighteenth century (Cohn JR, 2008). Themost recent plague pandemic started in the 19th century and began in the Yunnan province ofChina. It reached Hong Kong by 1894 and followed global trade routes to achieve a nearworldwide distribution (Stenseth et al., 2008). Since then plague has persisted in rodentpopulations in many areas of the world and continues to cause both isolated human cases andlocal epidemics."

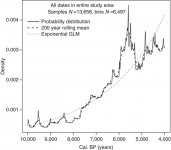

"Our perception of the evolutionary history of Y. pestis was changed substantially by arecent report of two reconstructed genomes from Central Asian Bronze Age steppenomads/pastoralists (~4,729 cal BP and ~3,635 cal BP, respectively) and molecular Y. pestissignatures in an additional five individuals from Eurasia (~4,500 to 2,800 BP) suggesting thepresence of plague in human populations over a diffuse geographic range prior to the firsthistorically recorded pandemics. Phylogenetic analysis of the two reconstructed Y. pestisgenomes from the Altai region shows that they occupy a phylogenetic position ancestral to allmedieval and extant Y. pestis strains, though this branch was not adequately resolved."

"In our dataset we identified four strong positives from three different locations datingfrom the Late Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age: one sample from the Lithuanian site Gyvakarai(Gyvakarai1), one sample from the Estonian site Kunila (KunilaII) and two samples fromAugsburg, Germany."

"The four prehistoric genomes presented here are the first complete Y. pestis genomes from theLate Neolithic and Bronze Age in Europe. They form a distinct clade with the previouslyreconstructed Central Asian Bronze Age Y. pestis genomes, confirming that all Late Neolithicand Bronze Age genomes reconstructed so far originated from a common ancestor. The oldestgenome RISE509 (Rasmussen et al., 2015) occupies the most basal position of all Y. pestis."

From a later period, but you get the idea:

Well, that about seals the deal for me. No wonder it didn't matter that Corded Ware had no bronze weapons until the very end, and barely even any copper.

Maybe by the time they crossed the Alps most of it had burned out?

See:

http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/12/15/094243

"Molecular signatures of Yersinia pestis were recently identified in prehistoric Eurasian individuals, thus suggesting Y. pestis might have caused some form of plague in humans prior to the first historically documented pandemic. Here, we present four new Y. pestis genomes from the European Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (LNBA) dating from 4,500 to 3,700 BP. We show that all currently investigated LNBA strains form a single genetic clade in the Y. pestis phylogeny that appears to be extinct today. Interpreting our data within the context of recent ancient human genomic evidence, which suggests an increase in human mobility during the LNBA, we propose a possible scenario for the spread of Y. pestis during the LNBA: Y. pestis may have entered Europe from Central Eurasia during an expansion of steppe pastoralists, possibly persisted within Europe until the mid Bronze Age, and moved back towards Central Eurasia in subsequent human population movements."

"it is assumed that plague affected human populations in three pandemic waves. The first, the Plague of Justinian,starting in the 6th century AD, was followed by multiple epidemic outbreaks in Europe and theMediterranean basin, and has been associated with the weakening and decay of the Byzantineempire (Russell, 1968). The second plague pandemic first struck in the 14th century with theinfamous ‘Black Death’ (1347-1352), which again spread from Asia to Europe seemingly alongboth land and maritime routes (Zietz and Dunkelberg, 2004). It is estimated that this initialonslaught killed 50% of the European population (Benedictow, 2004). It was followed byoutbreaks of varying intensity that lasted until the late eighteenth century (Cohn JR, 2008). Themost recent plague pandemic started in the 19th century and began in the Yunnan province ofChina. It reached Hong Kong by 1894 and followed global trade routes to achieve a nearworldwide distribution (Stenseth et al., 2008). Since then plague has persisted in rodentpopulations in many areas of the world and continues to cause both isolated human cases andlocal epidemics."

"Our perception of the evolutionary history of Y. pestis was changed substantially by arecent report of two reconstructed genomes from Central Asian Bronze Age steppenomads/pastoralists (~4,729 cal BP and ~3,635 cal BP, respectively) and molecular Y. pestissignatures in an additional five individuals from Eurasia (~4,500 to 2,800 BP) suggesting thepresence of plague in human populations over a diffuse geographic range prior to the firsthistorically recorded pandemics. Phylogenetic analysis of the two reconstructed Y. pestisgenomes from the Altai region shows that they occupy a phylogenetic position ancestral to allmedieval and extant Y. pestis strains, though this branch was not adequately resolved."

"In our dataset we identified four strong positives from three different locations datingfrom the Late Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age: one sample from the Lithuanian site Gyvakarai(Gyvakarai1), one sample from the Estonian site Kunila (KunilaII) and two samples fromAugsburg, Germany."

"The four prehistoric genomes presented here are the first complete Y. pestis genomes from theLate Neolithic and Bronze Age in Europe. They form a distinct clade with the previouslyreconstructed Central Asian Bronze Age Y. pestis genomes, confirming that all Late Neolithicand Bronze Age genomes reconstructed so far originated from a common ancestor. The oldestgenome RISE509 (Rasmussen et al., 2015) occupies the most basal position of all Y. pestis."

From a later period, but you get the idea:

Well, that about seals the deal for me. No wonder it didn't matter that Corded Ware had no bronze weapons until the very end, and barely even any copper.

Maybe by the time they crossed the Alps most of it had burned out?