We can’t assume. The letter “g” did not exist in early Latin alphabet. This implies that early Latin lacked the consonant “g”, and like etruscans did not distinguish b/p, d/t, g/k, early latins did not distinguish g/k. The consonant “g” was developed later by latins either because of contacts with other peoples (languages) or as a result of internal development of Latin. If the Latin alphabet was developed two or three centuries earlier, I’m quite sure that the letters “b” and “d” could have not figured too.

I am sorry to say this, but as Segia2 already said, you have a completely wrong assumption there. The letter 'g' did not exist in early Latin because the Romans adopted the Etruscan alphabet, and the Etruscans didn't distinquish between /g/ or /k/. Indeed, the Romans adopted the other Etruscan convention of using 'q' to represent 'k' before 'u' to represent the 'kw' sound in Latin, and as mentioned we even today have kept this convention (English 'question', 'queen').

One critical issue about

sound laws is that they

have no memories. So assuming for a moment that Latin indeed merged PIE *g and *k at an earlier point, there is no way how Latin at a later point could have separated *g and *k again because a language has no memory of sound changes, because clearly Latin *g and *k correspond with PIE *g (and *g´) and *k (and *k´). The only reasonable assumption here is that early Latin did indeed distinguish between /k/ and /g/, while the early Latin writing system didn't.

Even the sound inventories of today’s European languages have some differences (of course not so much, but there is). In my opinion, the lack of sounds “b”, “d”, “g” in Etruscan does not mean that it can not be an IE language just for that reason. If Etruscan was an isoglose, be sure that almost no Etruscan word could be found in today’s European languages.

What do you mean by 'isoglose'? By the way, this is the case: we

do find almost no word in today's European languages.

Such similar cases are numerous in all European languages. And not only for the shift *t > *d but for the shifts *p > *b and *k > *g too. This is also one more reason to believe in the extraordinary impact of Etruscan in almost all European languages. So, if we need to establish the hypothesis that in some cases German *t corresponds with PIE *d (and it really does), we need no hypothesis to prove that in such cases German *t corresponds (and it really fits) with Etruscan *t.

Because Etruscans did not distinguish b/p, d/t and g/k, it’s quite logical that Etruscan *p either corresponds with PIE *b or it fits with PIE *p; Etruscan *t either corresponds with PIE *d or it fits with PIE *t; Etruscan *k either corresponds with PIE *g or it fits with PIE *k.

In the same way as German *t either corresponds with PIE *d (in some cases), or it fits with PIE *t (in other cases).

And if (in return) I ask you the very same question WHICH ONE IS IT, the only answer would be: BOTH OF THEM!

I’m affraid I’m unable for a better explanation, so I wish you understand.

Actually, Indo-European is constructed with a much larger inventory of sounds which have various reflexes in various Indo-European languages. You have five series of stop sounds in total in PIE, each with an unvoiced, a voiced and a voiced+aspirated consonant:

*p, *b, *bh

*t, *d, *dh

*k, *g, *gh

*k´, *g´, *g´h

*kw, *gw, *gwh

Which leave for some example the following reflexes in various branches of Indo-European:

- in the Centum languages (Celtic, Germanic, Greek, Italic and Tocharian) *k´, *g´, *g´h from PIE are merged with *k, *g and *gh respectively, whereas in the Satem languages (Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranic) they are turned into fricative sounds instead.

- in the Celtic languages *p from PIE is generally lost (compare Irish 'Athair' vs. Latin 'Pater'). *gw is shifted to *b (compare Gaulish 'bena' and Irish 'bean' with English 'queen'), and *bh, *dh and *gwh become /b/, /d/ and /gw/ (but only after *gw > *b, obviously).

- In Latin, *bh yields *f at the beginning of a word, but *b in the middle of a word, which is why it is 'frater' in Latin, but 'bratir' in Gaulish and 'brother' in English.

- in the ancient Greek language, *bh, *dh and *gh are devoiced to /ph/, /th/ and /kh/ (represented by the letters Phi, Theta and Chi respectively), and later shifted to /f/, /θ/ and /x/ respectively.

- Sanskrit retains *bh, *dh and *gh.

- the Germanic languages make a chain shift (called 'Grimm's Law' or the 'First Germanic Sound Shift'), in which:

*bh > *b, *b > *p, *p > *f

*dh > *d, *d > *t, *t > *θ

*gh > *g, *g > *k, *k > *x (later *h)

A typical example would be the English words 'father' vs. Latin 'pater' or 'hound' vs. 'canis', Latin 'centum' vs. English 'hundred', and so on.

- Albanian, without exception, merged *bh, *dh, *gh, *g´h with *b, *d, *g, *g´ respectively. *g´ later became *ð while *k´ became *θ (which is why Albanian is a Satem language). However, many additional Albanian sound shifts are based on where specifically in a word is sound located:

For example PIE *kw yields /k/ in Albanian in most cases, but yields /s/ before positions where a front vowel (i or e) stood in PIE. For this reason, PIE *

kwetores (four) yields Albanian '

katër' but PIE *pen

kwe yields *pe

së.

None of the Albanian sound correspondences would really make

any sense if you take Etruscan as the source language, because as mentioned Etruscan is fundamentally non-Indo-European. One very critical issue I would like to bring up here is the absence of /o/ in Etruscan, which is found in PIE as well as Albanian (as well as most IE language).

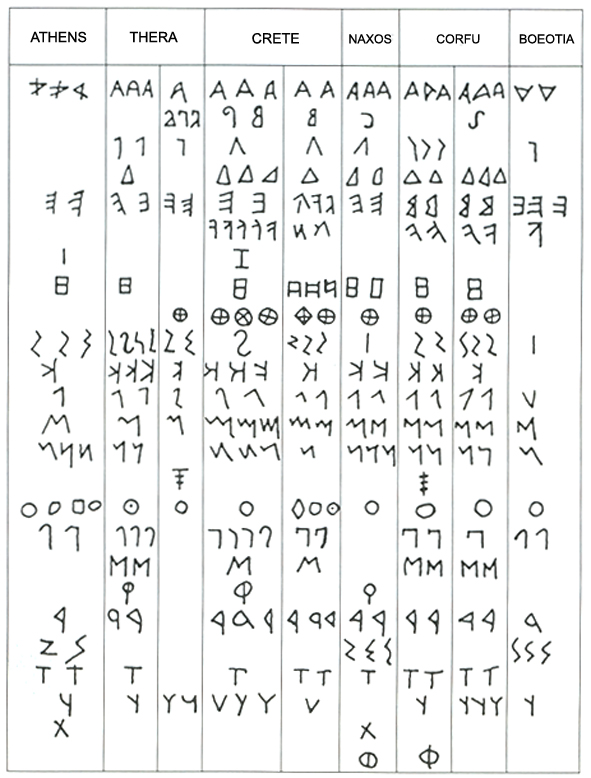

Some peoples adopted writing systems that didn't possess their phonologic inventary, just for geographical proximity. The fact that some of them didn't develop new letters doesn't imply that their language lacked certain sounds. In the iberian peninsula you can see examples of this, such as celtiberian language adopting iberian writing system (wich didn't distinguish between voiced and voiceless consonants, hadn't consonantic groups bl/br/kl....)

The differentiated use of latin /g/ and /k/ isn't arbitrary and can't be explained as an internal evolution. Why to use "centum" and "gens" if there isn't a phonetic rule that would lead to a differentiated solution?

I absolutely agree with your post here except for a small nitpick: Iberian, just like Celtiberian distinguished between voiced and voiceless stops, but Tartessian (the language for which the oldest writing system of Iberia was actually developed) didn't make such a distinction. It's also in my opinion the most straightforward reason why Tartessian is not a Celtic language. To quote

Zeidler, the Tartessian script is hardly suitable for representing an Indo-European language.