Taranis

Elite member

the quote is from bob quin' book. He was wandering if Gaelic languages were celtic languages and Gaelic languages survived dispite 1000 years of cultural colonisation and suppression, why didn'g Gaelic languages survive in central and western europe. he concluded that if Celts even existed the reason Gaelic didn't survive in the mainland europe is because celts didn't speak s Gaelic language. Which language they did speak he didn't go into as his interest is Gaelic and not Celtic. But he states this many times that Gaelic languages are not Celtic and did not come to british isles from mainland europe but from Spain and north and west Africa.

I'm under the impression that this Bob Quinn is neither aware of the history of the Gaelic languages, nor has he an understanding of linguistics. Would he have this, he'd be aware that what he claims there is complete nonsense. I'm sorry that I have to say it like that, but it's true.

By the time of the Romans, the Irish language did not yet exist in a form that we would recognize as such.

they were nor refered to as celts by all knowing romans and greeks but somehow they speek celtic language? how can this be? and again we come to the question: "what is a celtic language? and how did we come to the definition or the celtic language"

The ancient Greeks and Romans were neither all-knowing, nor were they free of mistakes. But in this specific case, the explanation is a different one: they were actually aware of the high degree of similarity of languages and culture between the British Isles and Gaul (both Tacitus, in his Agricola, and Julius Caesar, in his commentaries on the Gallic War, mention this actually!). Where the difference comes from is that the Romans didn't think in the dimensions of modern-day ethno-linguistic concepts. For them, Britain and Gaul were two distinct geographic entities, and they treated it's denizens as such.

Additionally, just because people speak related, even very similar languages doesn't mean that they identify as a common identity: to pick a few modern examples, take the Dutch and the Germans, the Danes and the Norwegians, or the English and the Americans.

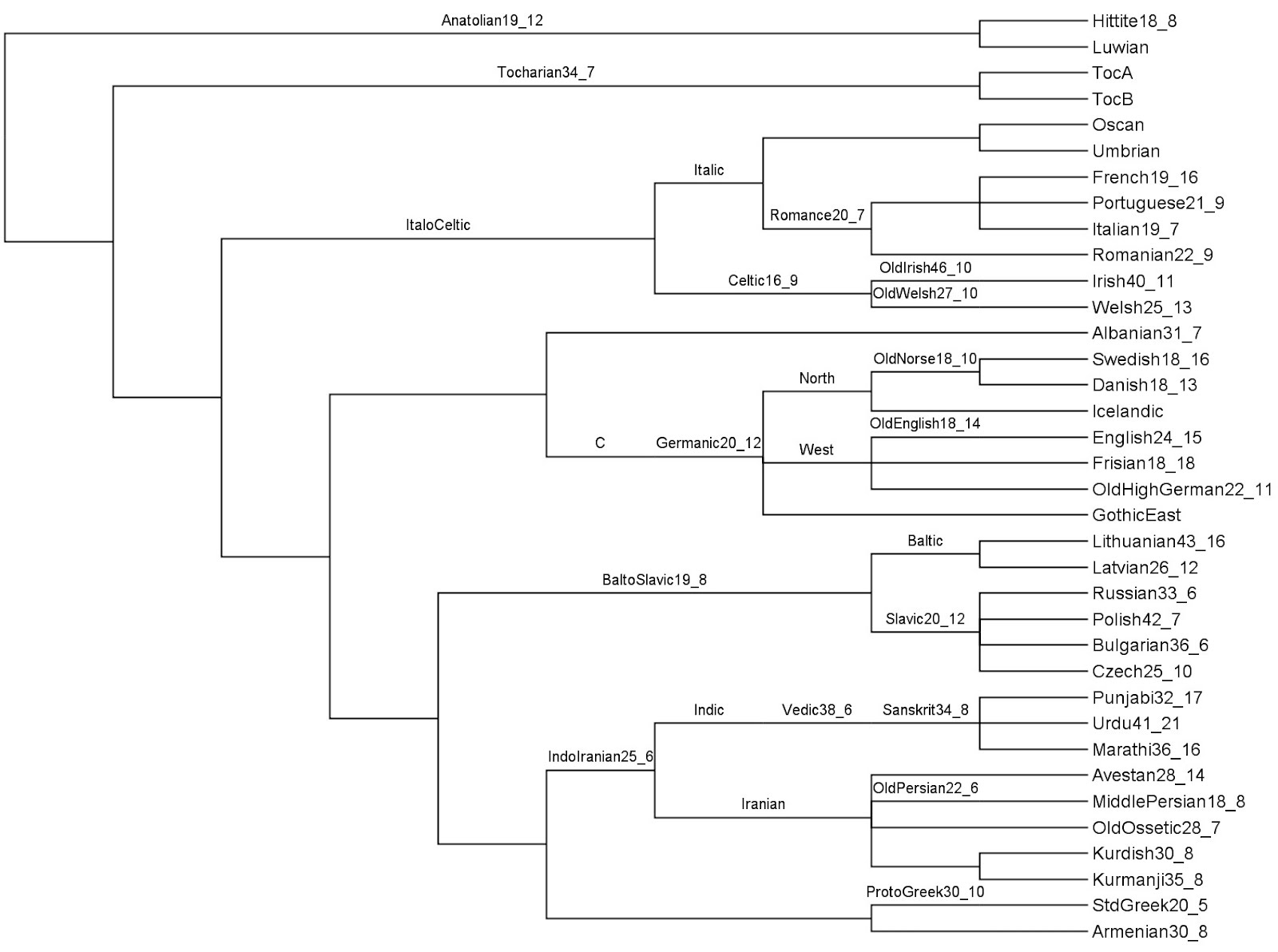

As for what a Celtic language is: in the linguistic context, any language family is defined by a common set of sound changes that all languages in this family have in common. In the case of the Celtic languages, there is a number of sound changes that all Celtic languages have in common and that sets them apart from the other branches of Indo-European. If you go further down, you can establish sound laws for instance all Brythonic languages have in common which puts them apart from the other Celtic languages.

it is actually the oposite. irish language is over 5000 years old and the celtic elements are relative newcommers.

That's impossible. Where does this 5000 years figure come from? The Irish language is only attested from the 4th century AD onward. As I said, the oldest testimony of Irish is the Ogham inscriptions.

i really don't want to go into this here this is a thread on veneti and wendi, but we can continue this discusion here or on another thread if you want.

This discussion about the Gaels is actually somewhat related to the "Veneti", at least the Gaulish Veneti. As another Eupedia board member pointed out (I don't recall whom, but I would like to give said person hereby credit), the word "Gael" is actually in itself an exonym, that is, a foreign designation for the Irish people, and it is actually derived from Medieval Welsh "Guoidel", meaning "pirate". So, the Irish did not designate themselves as "Gaels" before the Medieval Ages. There is actually another term attested in Old Irish, "Féni", which means "compatriots" or "Irishmen". Now, this term is actually cognate of the "wen-" in the tribal name "Veneti".