The Roman East Empire was an multiethnic empire. Emperors who ruled had different nationalities.

Constantine the Great

Flavius Valerius Constantinus, as he was originally named, was born in the city of Naissus, (today

Niš, Serbia) part of the

Dardania province of

Moesia, on 27 February of an uncertain year,

[28] probably near 272.

[29] His father was

Flavius Constantius,

a native of Dardania province of Moesia (later

Dacia Ripensis).

He Was Illyrian.

The first Roman emperor to

claim conversion to

Christianity,

[notes 4] Constantine played an influential role in the proclamation of the

Edict of Milan, which decreed tolerance for Christianity in the empire. He called the

First Council of Nicaea in 325, at which the

Nicene Creed was professed by Christians.

Foundation of Constantinople

Eventually, however, Constantine decided to work on the city of

Byzantium, which offered the advantage of having already been extensively rebuilt on Roman patterns of urbanism, during the preceding century, by

Septimius Severus and

Caracalla, who had already acknowledged its strategic importance.

[206] The city was thus founded in 324,

[207] dedicated on 11 May 330

[207] and renamed

Constantinopolis ("Constantine's City" or

Constantinople in English).

Colossal marble head of Emperor Constantine the Great, Roman, 4th century

Following his death, his body was transferred to Constantinople and buried in the

Church of the Holy Apostles there.

[260] He was succeeded by his three sons born of Fausta,

Constantine II,

Constantius II and

Constans. A number of relatives were killed by followers of Constantius, notably Constantine's nephews

Dalmatius (who held the rank of Caesar) and

Hannibalianus, presumably to eliminate possible contenders to an already complicated succession. He also had two daughters,

Constantina and

Helena, wife of

Emperor Julian.

[261]

Justin I

Justin was a peasant and a swineherd by occupation

[2] from the region of

Dardania, which is part of the

Diocese of Illyricum.

[3]

He was born in a

hamlet Bederiana near

Naissus (modern

Niš, South

Serbia). The

Justinian Dynasty descend from him

.

He Was Illyrian.

Tremissis of Emperor Justin I

Justinian I or Justinian the Great

Justinian was born in

Tauresium[12] around 482. The

cognomen Iustinianus which he took later is indicative of adoption by his uncle

Justin.

[17] During his reign, he founded

Justiniana Prima not far from his birthplace, today in South East Serbia.

[18][19][20] His mother was Vigilantia, the sister of Justin. Justin, who was in the imperial guard (the

Excubitors) before he became emperor,

[21] adopted Justinian, brought him to

Constantinople, and ensured the boy's education.

[21]

Justinian (b. 483) and consequently Vigilantia Dulcissimus were children of a sister Vigilantia Sabbatius (b. a. 455) of

Justin I (b. a. 450, r. 518–527), founder of the

Justinian Dynasty. T

he family originated in Bederiana, near Naissus (modern Niš in Serbia) in Dacia Mediterranea.[4] Procopius, Theodorus Lector, Zacharias Rhetor, Victor of Tunnuna, Theophanes the Confessor and Georgios Kedrenos consider Justin and his family Illyrians.

As a ruler, Justinian showed great energy. He was known as "the emperor who never sleeps" on account of his work habits.

He Was Illyrian.

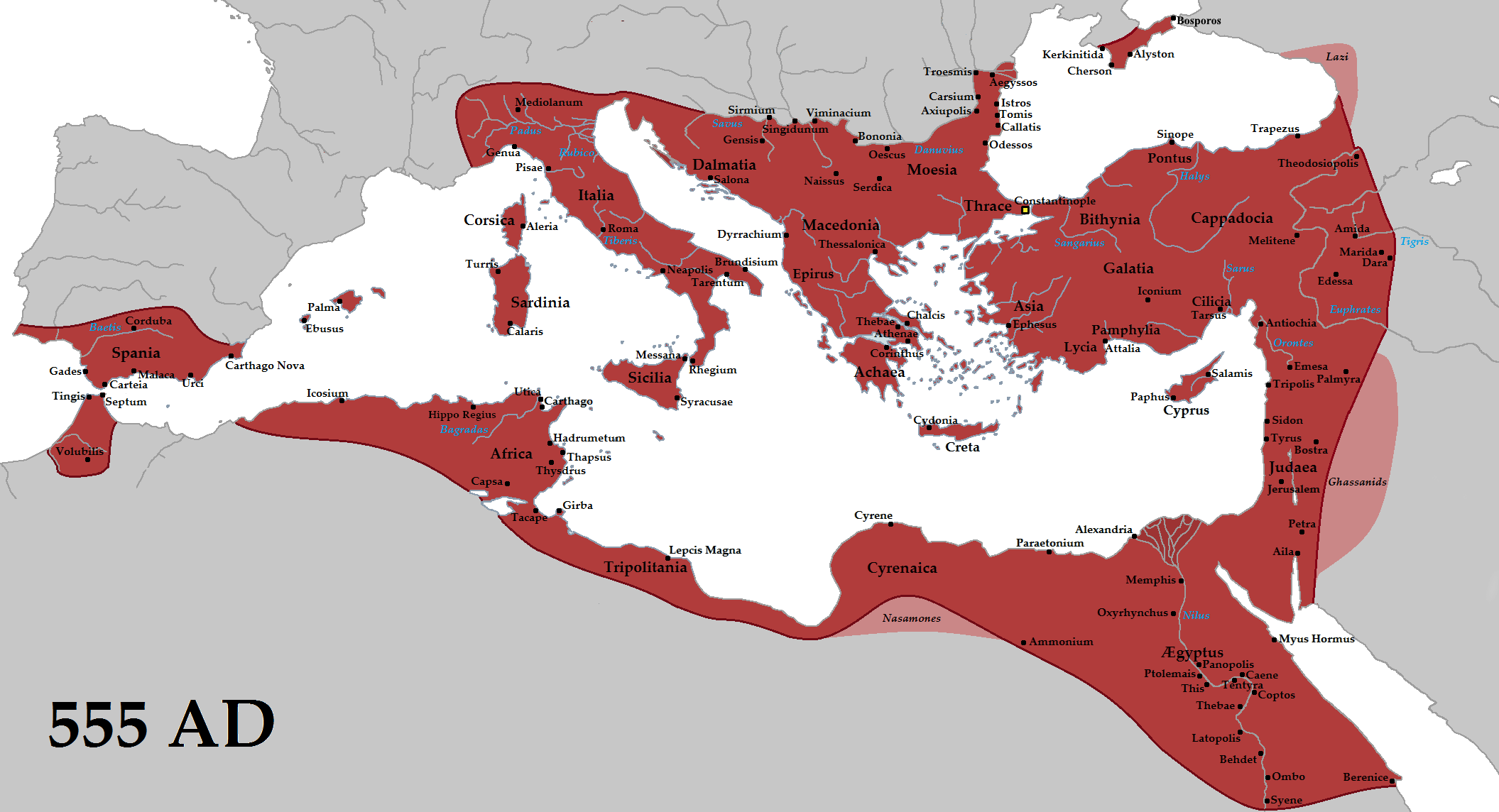

He increased the Byzantine Empire due to its maximum.

Emperor Justinian reconquered many former territories of the Western Roman Empire, including

Italy,

Dalmatia, Africa, and southern

Hispania.

He made this with the help of Illyrians generals, the most distinguished was .

Flavius Belisarius was probably born in

Germane or

Germania, a fortified town (some archaeological remains exist) on the site of present day

Sapareva Banya in south-west

Bulgaria, in the borders of

Thrace and

Illyria.

Belisarius may be this bearded figure

[1] on the right of Emperor

Justinian I in the mosaic in the

Church of San Vitale,

Ravenna, which celebrates the reconquest of Italy by the

Byzantine army. Compare Lillington-Martin (2009) page 16.

He Was Illyrian.

Justinian I built in the territory of Illyria 167 castle, which together with the mountainous terrain helped Illyrians during the invasions of the barbarians and the fist wave of slavic invasion.The

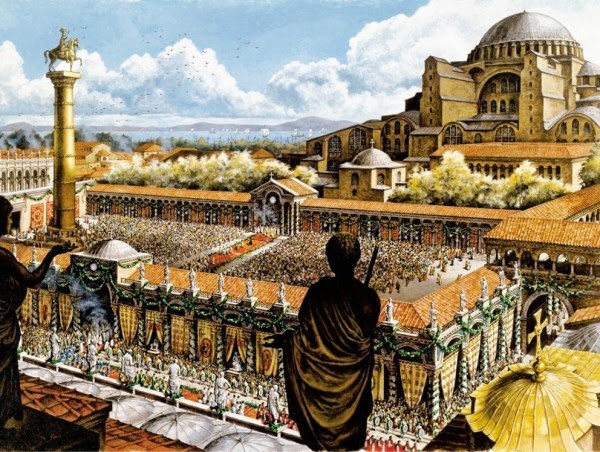

Justinian Dynasty made the Empire strong and beautifull, during the Justinian I started the construction of Hagia Sophia

whose works were completed during the reign of Emperor

Justin II (565–578).His reign also marked a blossoming of Byzantine culture, and his building program yielded such masterpieces as the church of

Hagia Sophia, which was to be the center of

Eastern Orthodox Christianity for many centuries.

During this period the empire retained its Latin character. Later emperors with different nationalities ruled the Byzantine Empire.

The last Emperor was

Constantine XI Dragaš Palaiologos.

He was half serbian, 1/4 italian and the rest i don`t know.