Byzantine Albania

[h=3]Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081)[/h]

The Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard was an elite unit of the Byzantine Army in 10th to the 14th centuries, whose members served as personal bodyguards of the Byzantine Emperors.

.

The guard was first formed under Emperor Basil II in 988, following the Christianization of Kievan Rus' by Vladimir I of Kiev. Vladimir, who had recently usurped power in Kiev with an army of Varangian warriors, sent 6,000 men to Basil as part of a military assistance agreement.

.

This man is of Scandinavian origin, migrated in Kievan Rus kingdom. The shield depicts the crow-symbol of god Odin and he holds Danish Axe. Greaves, hand protection, chest leather strips and pteryges, are obviously Byzantine, borrowed from the Imperial arsenal.

Normans vs Byzantines - The Battle of Dyrrhachium

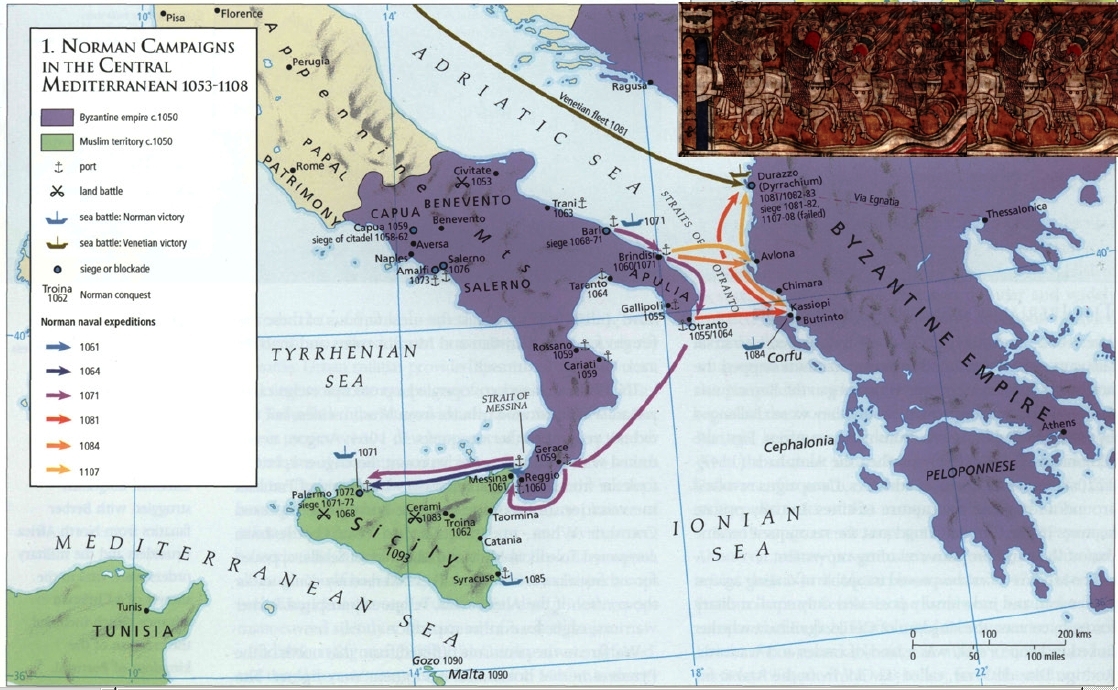

- In 1071 the Romans experienced their greatest defeat ever at the Battle of Manzikert. The eastern provinces of the Empire were being overrun by Muslim Turks. It was at this moment that the Normans chose to invade the Roman Western provinces to carve out an even greater empire for themselves at the expense of fellow Christians.

The Battle of Dyrrhachium (near present-day Durrës in Albania) took place on October 18, 1081 between the Roman Empire, led by the Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, and the

Normans of southern Italy under Robert Guiscard, Duke of Apulia and Calabria. The battle was fought outside the city of

Dyrrhachium (also known as

Durazzo), the Byzantine capital of Illyria.

Following the Norman conquest of Byzantine Italy and Saracen Sicily, the Byzantine emperor, Michael VII Doukas, betrothed his son to Robert Guiscard's daughter and sent her to Constantinople.

Guiscard’s ambitions drew him east, for the new Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus was deeply involved in recovering Asia Minor after a disastrous defeat by the Turks at Manzikert in 1071.

Prelude

Guiscard conscripted all men of a fighting age into the army, which he refitted. He sent his son Bohemond with an advance force towards what is modern Albania. Bohemond landed at Aulon, with Guiscard following shortly.

The Norman fleet of 150 ships including 60 horse transports set off towards the Byzantine Empire at the end of May 1081. The army numbered 30,000 men, backed up by 1,300 Norman knights. The fleet sailed to

Avalona in Byzantine territory; they were joined by several ships from

Ragusa, a republic in the Balkans who were enemies of the Byzantines.

Robert soon left Avalona and sailed to the island of Corfu, which surrendered because of a small garrison. Having won a bridgehead and a clear path for reinforcements from Italy, he advanced on the city of Dyrrhachium, the capital and chief port of Illyria.

The city was

well defended on a long, narrow peninsula running parallel to the coast, but separated by marshlands. Guiscard brought his army onto the peninsula and pitched camp outside the city walls. However, as Robert's fleet sailed to Dyrrhachium, it was hit by a storm and lost several ships

Meanwhile, when Alexius heard that the Normans were preparing to invade Byzantine territory, he sent an ambassador to the Doge of Venice, Domenico Selvo, requesting aid and offering trading rights in return.

The Doge, alarmed by Norman control of the Strait of Otranto, took command of the Venetian fleet and sailed at once, surprising the Norman fleet under the command of Bohemond as night was falling. The Normans counter-attacked tenaciously, but their inexperience in naval combat betrayed them. The experienced Venetian navy attacked in a close formation known as "sea harbour" and together with their use of

Greek fire "bombs", the Norman line scattered, and the Venetian fleet sailed into Dyrrhachium's harbour.

|

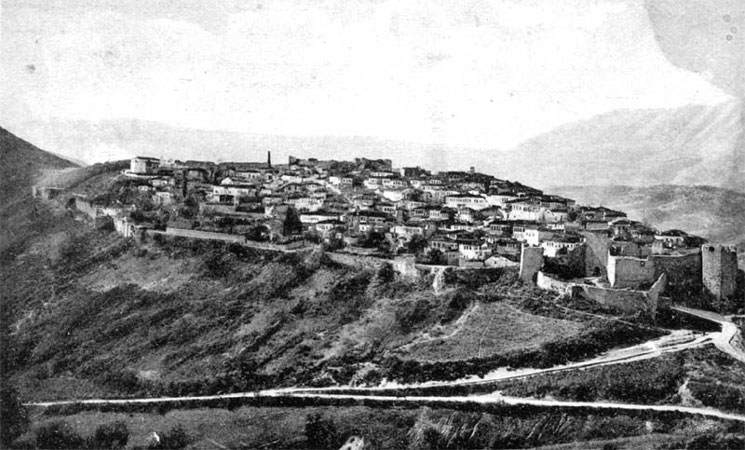

Durrës Castle, Albania.

Durrës (Dyrrhachium) was the center of a battle between invading Normans and the Roman Empire. The castle was built by Emperor of the Byzantine Empire Anastasius I originating from Durres, which transformed it into one of the most fortified cities on the Adriatic.

.

The Roman emperor Caesar Augustus made the city a colony for veterans of his legions following the Battle of Actium, proclaiming it a civitas libera (free town). In the 4th century, Dyrrachium was made the capital of the Roman province of Epirus nova. |

|

| Near the port of Durrës is the ancient Byzantine city wall. |

Siege of Dyrrhachium

Robert was not discouraged by this naval defeat, and began his siege of Dyrrhachium. In command of the garrison at Dyrrhachium was the experienced general George Palaeologus, sent by Alexius with orders to hold out at all costs while Alexius himself mustered an army to relieve the city.

Meanwhile, a Byzantine fleet arrived and – after joining with the Venetian fleet – attacked the Norman fleet, which was again routed. The garrison at Dyrrhachium managed to hold out all summer, despite Robert's catapults, ballistae and siege tower. The garrison made continuous sallies from the city; on one occasion, Palaeologus fought all day with an arrowhead in his skull. Another sally succeeded in destroying Robert's siege tower.

Robert's camp was struck by disease; according to contemporary historian

Anna Comnena up to 10,000 men died, including 500 knights.

|

Norman infantry reenactors.

.

"Not being satisfied with the men who had served in his army from the beginning and had experience in battle, he formed a new army, made up of recruits without any consideration of age. From all quarters of Lombardy and Apulia he gathered them, over age and under age, pitiable objects who had never seen armour in their dreams, but then clad in breastplates and carrying shields, awkwardly drawing bows to which they were completely unused and following flat on the ground when they were allowed to march."

Princess Anna Comnena

describing Robert Guiscard's conscription. |

Norman Cavalry Charge

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odxwYPrtXUU&feature=player_embedded

Norman Cavalry Attacking

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ElykPHD6lFw

|

Norman Cavalry.

"Alexius was undoubtedly a good tactician, but he was badly let down by the indisciplined rush to pursue the beaten enemy wings, a cardinal sin in the Byzantine tactical manuals. He failed to take adequate account of the effectiveness of the Norman heavy cavalry charge, which punched through his lines with little resistance."

Historian John Haldon's assessment of the battle |

The situation of the Dyrrhachium garrison grew desperate because of the effects of Norman siege weapons. Alexius learned of this while he was in Salonica with his army so he advanced in full force against the Normans.

According to Comnena, Alexius had about 20,000 men. It consisted of Thracian and Macedonian tagmata, which numbered about 5,000 men; the elite excubitors and

vestiaritai units, which numbered around 1,000 men; a force of

Manichaeans which comprised 2,800 men, Thessalian cavalry, Balkan conscripts, Armenian infantry and other light troops.

As well as the native troops, the Byzantines were joined by 2,000 Turkish and 1,000 Frankish mercenaries, about 1,000 Varangians and 7,000 Turkish auxiliaries sent by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm. Alexius also withdrew the tagmas from

Heraclea Pontica and the remaining Byzantine holdings in Asia Minor and by doing so, he effectively left them to be overrun by the Turks.

Alexius advanced from Salonica and pitched camp on the river Charzanes near Dyrrhachium on October 15. He held a war council there and sought advice from his senior officers; among them was George Palaeologus, who had managed to sneak out of the city. A majority of the senior officers, including Palaeologus, urged caution, noting that time was with the Emperor. Alexius, however, favoured an immediate assault, hoping to catch Guiscard's army from the rear, while they were still besieging the city. Alexius moved his army to the hills opposite the city, planning to attack the Normans the next day.

Guiscard, however, had been informed of Alexius' arrival by his scouts and on the night of October 17, he moved his army from the peninsula to the mainland. Upon learning of Guiscard's move, Alexius revised his battle plan. He split his army into three divisions, with the left wing under the command of

Gregory Pakourianos, the right wing under the command of

Nikephoros Melissenos, and himself in command of the centre. Guiscard formed his battle line opposite Alexius's, with the right wing under the command of the Count of Giovinazzo, the left under Bohemond and Guiscard facing Alexius in the centre.

Bad Day at Dyrrhachium- A Varangian Perspective

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNWuHQW5iyo&feature=player_embedded

The Varangians had been ordered to march just in front of the main line with a strong division of archers a little behind them. The archers had been commanded to move in front of the Varangians and fire a volley before retreating behind them. The archers continued this tactic until the army neared contact.

As the opposing armies closed in, Guiscard sent a detachment of cavalry positioned in the centre to feint an attack on the Byzantine positions. Guiscard hoped the feint would draw up the Varangians; however, this plan failed when the cavalry was forced back by the archers.

The Norman right wing suddenly charged forward to the point where the Byzantine left and centre met, directing its attack against the Varangian left flank. The Varangians stood their ground while the Byzantine left, including some of Alexius' elite troops, attacked the Normans. The Norman formation disintegrated and the routed Normans fled towards the beach. There, according to Comnena, they were rallied by Guiscard's wife, Sikelgaita, described as "like another Pallas, if not a second Athena".

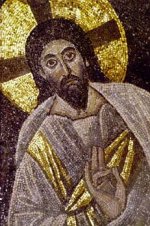

|

| Emperor Alexios I Komnenos |

Byzantine collapse

In the meantime, the Byzantine right and centre had been engaging in skirmishes with the Normans opposite them. However, with the collapse of the Norman right, the knights were in danger of being outflanked.

At this point, the Varangians (mainly Anglo-Saxons who had left England after the Norman Conquest) joined in the pursuit of the Norman right. With their massive battle axes, the Varangians attacked the Norman knights, who were driven away after their horses panicked. The Varangians soon became separated from the main force and exhausted so they were in no position to resist an assault.

Guiscard sent a strong force of spearmen and crossbowmen against the Varangian flank and inflicted heavy casualties on them. The few remaining Varangians fled into the church of the Archangel Michael. The Normans immediately set the church on fire, and all Varangians perished in the blaze.

Meanwhile, George Palaeologus sortied out of Dyrrhachium, but failed to save the situation. Worse, Alexius's vassal, King

Constantine Bodin of

Duklja, betrayed him. The Turks who had been lent to him by the Seljuk Sultan

Suleyman I followed Constantine's example and deserted.

Deprived of his left wing (still in pursuit of the Norman right), Alexius was exposed in the centre. Guiscard sent his heavy cavalry against the Byzantine centre. They first routed the Byzantine skirmishers before breaking into small detachments and smashing into various points of the Byzantine line. This charge broke the Byzantine lines and caused them to rout. The imperial camp, which had been left unguarded, fell to the Normans.

|

Byzantine Tagmata

The Roman Army at Dyrrhachium included

Thracian and Macedonian Tagmata, which

numbered about 5,000 men. |

Alexius and his guards resisted as long as they could before retreating. As they retreated, Alexius was separated from his guard and was attacked by Norman soldiers. While escaping, he was wounded in his forehead and lost a lot of blood, but eventually made it back to

Ohrid, where he regrouped his army.

Aftermath

The battle was a heavy defeat for Alexius. Historian Jonathan Harris states that the defeat was "every bit as severe as that at Manzikert." He lost about 5,000 of his men, including most of the Varangians. Norman losses are unknown, but John Haldon claims they are substantial as both wings broke and fled. Historian Robert Holmes states: "The new knightly tactic of charging with the lance

couched – tucked firmly under the arm to unite the impact of man and horse – proved a battle-winner."

George Palaeologus had not been able to re-enter the city after the battle and left with the main force. The defense of the citadel was left to the Venetians, while the city itself was left to an Albanian, Komiskortes.

In February 1082, Dyrrhachium fell after a Venetian or Amalfian citizen opened the gates to the Normans. The Norman army proceeded to take most of northern Greece without facing much resistance. While Guiscard was in

Kastoria, messengers arrived from Italy, bearing news that Apulia, Calabria, and Campania were in revolt.

He also learned that the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV, was at the gates of Rome and besieging Pope Gregory VII, a Norman ally. Alexius had negotiated with Henry and given him 360,000 gold pieces in return for an alliance. Henry responded by invading Italy and attacking the Pope. Guiscard rushed to Italy, leaving Bohemond in command of the army in Greece.

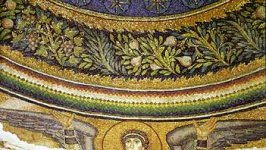

|

Varangian Guards.(in ceremonial costumes)

Nea Moni-Chios Monastery-1040's. |

Alexius, desperate for money, ordered the confiscation of all the church's treasure. With this money, Alexius mustered an army near Thessalonica and went to fight Bohemond. However, Bohemond defeated Alexius in two battles: one near

Arta and the other near

Ioannina.

This left Bohemond in control of Macedonia and nearly all of Thessaly. Bohemond advanced with his army against the city of

Larissa. Meanwhile, Alexius had mustered a new army and with 7,000 Seljuk Turks sent by the Sultan, he advanced on the Normans at Larissa and defeated them. The demoralised and unpaid Norman army returned to the coast and sailed back to Italy.

Meanwhile, Alexius granted the Venetians a commercial colony in Constantinople, as well as exemption from trading duties in return for their renewed aid. They responded by recapturing Dyrrhachium and Corfu and returning them to the Byzantine Empire. These victories returned the Empire to its previous status quo and marked the beginning of the Komnenian restoration

The Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081 A.D.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=azkoIZ4l9Ik&feature=player_embedded