Thank you traveller.

If I understand this correctly, it is a matter to controll the progress of the reaction of the quicklime with water.

And at some point this reaction should be stopped, maybe by a shortage in moisture, so it can infiltrate and start again in the cracks when they become wet again?

The quicklime should be mixed and dispersed very well in the concrete.

I've first heared about this in self-healing fibre-reinforced polymer composites, which are very prone to cracks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-healing_material

Thanks for the link!

Apparently the quicklime particles have to be big enough not to hydrate completely.

This is a different process from the Roman undersea concrete:

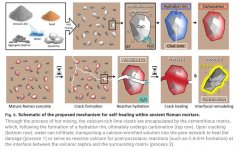

“Whereas previous evidence supports the formation of Al-tobermorite minerals in lime clasts of maritime structures due to the heat of the pozzolanic reaction (23), the results presented here suggest that, by contrast, when quicklime is introduced via hot mixing in terrestrial structures, the reaction is limited to the outer rim of the lime clast, encapsulating calcium-rich core structures within mortar matrix.”

It would require particle sizes that are “just right” to stay active over a long period but not jeopardize the strength and dimensions of the concrete/mortar, as well as much finer particles or prehydrated lime to achieve initial strength. Actually, using this as mortar to bind stones in a wall massive enough to be stable on its own might make more sense than a big chunk of concrete.

Still, I don’t think the self-healing can last through a longer period of crack formation as at some point all the active lime would be spent.