The claim that the Ringe tree topology supports the Steppe hypothesis rests especially on one particular node,which has also been taken as particularly important for contextualizing ancient DNA findings. The last major nodein the Ringe tree keeps Indo-Iranic and Balto-Slavic together in a single common branch until very late in thefamily’s divergence history, after all other main branches have split off. This has been taken to entail that theancestor of Indo-Iranic languages would likely have still been outside India and Iran, and further north on theSteppe, until a correspondingly late date. In Ringe’s chronology, the lineage ancestral to all Indic and Iraniclanguages remained undistinguished from the lineage ancestral to Baltic and Slavic languages until as late as c.2450 BC, i.e. less than a millennium before the time of Vedic, set by Ringe at 1500 BC. (It is not in fact universallyaccepted that Balto-Slavic itself is a valid node, although this is the majority view and in our analysis has a highposterior probability. For discussion, see (154).)

Even in Ringe’s own data-set, support for this last major node of [Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic] is very thin: it consistsof only three binary characters (while other characters conflict with any single tree). Each of these three charactersis highly questionable, and not considered probative by many other specialists. It is no widespread view that Indo-Iranic is most closely related to Balto-Slavic, or to any other particular branch (155).

One of Ringe’s three characters is cognacy in the meaning ‘all (plural)’. Cognacy between Indo-Iranic and Balto-Slavic languages is only partial here, however. Their ‘all’ words share only the morpheme *wi, followed by differentextensions: Indo-Iranic has *wikw o, Balto-Slavic has *wiso. Ringe opts to code both as state 5 (differentiated onlyby his 5a and 5b labels), rather than as different states 5 and 6. Furthermore, *wi reconstructs to Proto-Indo-European, so its use in this meaning may be a shared retention or a parallel semantic shift, and does not prove aunique, late [Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic] node.

The other two characters have been long debated in Indo-European research: one aspect of the centum/satemcontrast, and the ‘ruki rule’. Ringe does not follow the basic contrast between centum and satem languages. Hedefines his character P2 narrowly, as “full ‘satem’ development of dorsals”, i.e. in such a way as to apply not to allsatem languages, but only to Indo-Iranic and Balto-Slavic (and to explicitly exclude Armenian and Albanian: p. 104in (50)). This is taken as a definitive character, which specifically separates [Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic] from [Greek+ Armenian]. So in effect, Ringe’s preferred definition separates [Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic], to set the satemlanguage Armenian together with the non-satem Greek instead. (This is because the state for P2 full satem is absentin both, even though basic satem is present in Armenian and absent in Greek.) This contradicts and overrides thebasic centum/satem contrast, then, which is not used as a character in the Ringe data‐set. There is long-standingdebate on this issue, and a range of alternative hypotheses on how the patterns in the language data arose. Ringe’schoice of definition is subjective, as is his confidence that that particular definition can be taken as a probativephylogenetic character — necessarily inherited, rather than a parallel development or areal phenomenon — whileother definitions cannot. This interpretation does not enjoy consensus in the field.

The ‘ruki’ rule (Ringe’s character P3) is a sound change named for the phonological context that triggers it, namelythe set of sounds /r/, /u/, /k/ and /i/ (or in fact not just /k/, but also other dorsal stops). The sound change is thatoriginal Proto-Indo-European */s/ came to be articulated slightly further back in the mouth (‘retracted’), as /ʃ/instead. Cross-linguistically, /s/ > /ʃ/ is in itself a frequent sound change, but what most Indo-Iranic and Balto-Slavic languages share is that this change generally applied also in the same set of contexts, namely where */s/followed immediately after any of the ‘ruki’ set of sounds. Some analysts deem the /i/ and /u/ vowels, and theconsonants /r/ and dorsal stops (like /k/), to form a particular combination of contexts idiosyncratic and unusualenough that it can be considered unlikely that the same sound change in these same contexts could have arisenindependently twice. These analysts take it as more plausible that the retraction change arose only once, that is,along a single branch to a common ancestor of [Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic]. This is Ringe’s position.

However, /i/ and /u/ have in common that they are the two highest cardinal vowels, where the tongue comesclosest to the palate and velum respectively. And /k/ is also formed at the velum, by the back of the tongue actuallymaking full closure there. Other ‘dorsal’ stops are also defined as being articulated by the back of the tongue (the‘dorsum’) against the palate, velum or even further back at the uvula. As for /r/-sounds, in phonology these form anotoriously diverse set, including sounds articulated from palatal to uvular as the location of stricture. The precisephonetic realization of the /r/ phoneme in early Indo-European branches is uncertain. So in fact, /r/, /u/, /k/ and/i/ all lie on the ‘close’ and ‘back’ limits to the vowel space, where it maps onto the corresponding places ofarticulation for consonants (see Fig. 10.6 in (156), and (157)). Nor is the mixed set of vowel and consonant triggersso unusual, particularly given that in Proto-Indo-European /i/ and /u/ functioned largely as (sonorants) in anycase, i.e. as consonants. The ‘ruki’ contexts all have in common a location of stricture that can naturally draw thearticulation of a preceding /s/ sound to be retracted to /ʃ/, closer where dorsal stops and high vowels arethemselves articulated with the tongue (i.e. partial assimilation in place of articulation).

The ‘ruki’ set of contexts is thus not phonetically unmotivated or unusual for triggering a retraction of /s/. Otheranalysts consider the outputs to reflect a set of similar retraction changes that arose independently in parallel,rather than a single rule operating just once in a putative common Proto-Indo-Iranic-Balto-Slavic. There aremultiple indications that somewhat different, separate changes did indeed arise. According to some analyses, the‘ruki’ retraction of */s/ may also have applied partly in Albanian and to individual words in Armenian.Furthermore, the retraction did not operate identically or universally across Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iranic in anycase. Ringe himself recognizes several complications (p. 109 in (50)), while other authors discuss details andexceptions in (158) for Indic and in (159) for Iranic, for example.

Alternative analyses are possible because various more recent sound changes have obscured the evidence of whatmay or may not have happened at earlier stages. In many languages, original Proto-Indo-European */s/ in ‘ruki’contexts is found as other sounds, not /ʃ/, and it is not always knowable whether an original */s/ > /ʃ/ retractionhad or had not already happened first. The retraction is observable in Lithuanian, for instance, but not in otherlanguages of the Baltic branch, so it is not clear whether the change had operated by the Proto-Balto-Slavic stage. InSlavic, the retracted /ʃ/ shifted again to /x/, whereas in Indic /ʃ/ shifted to contrastive retroflex /ʂ/. In Nuristani,Morgenstierne first noted that although original /s/ is often found changed to /ʂ/ as in Indic languages, this doesnot apply after the /u/ context, where original /s/ remained (160). As examples from Morgenstierne (withcorrections for Nuristani added here), in words for ‘mouse’ derived from Proto-Indo-European *múh2s with */s/,Indic languages have changed that /s/ ultimately to retroflex /ʂ/ (spelt in Indic as dotted ṣ), as for example in Vedicmūṣ- or Gawarbati muṣa. The cognate word in Nuristani languages, however, has /s/, without retraction to /ʂ/:Kâmviri and Kâta-vari both have /musˈa/ (realized phonetically as [muzˈɨ] and [musˈɨ] respectively), and Vâsi-varihas /müs/. Also in Nuristani, both after and before the /i/ context, original */s/ is found as /ʃ/, but through arelatively late sound change. For these /i/ contexts, strictly it cannot be known whether original ‘ruki’ changes hadalready applied, i.e. in a chain of /s/ > /ʃ/ > ‘Indic’ /ʂ/ and then back to Nuristani /ʃ/, but this raises questions ofparsimony and phonological motivation.

To be consistent with ‘ruki’ as evidence for an Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic node, one has to entertain the idea thatNuristani languages did actually inherit all the results of a full original ‘ruki’ change, but then reversed some of

those results by later sound changes: e.g. where found between vowels, /ʂ/ changed (‘back’) to /s/. Although thishas been hypothesized (161), the analysis includes faulty data on Nuristani languages, and proposes a sound changewhich — although convenient for defending a sweeping ruki rule — is unmotivated phonologically. It is unclearwhat phonetic preconditions should have caused such a reversal, nor why other instances of intervocalic *ṣ did nottherefore also become *s in Nuristani. For a more phonologically plausible alternative analysis of Nuristani “non-ruki *u”, not consistent with ruki as validly demonstrating an Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic node, see §4.2 in (162).

In sum, it is highly controversial whether the ‘ruki’ sound change is a genuine, single shared innovation (at aputative common Proto-Indo-Iranic-Balto-Slavic stage); many specialists consider it a series of independentparallel changes instead.

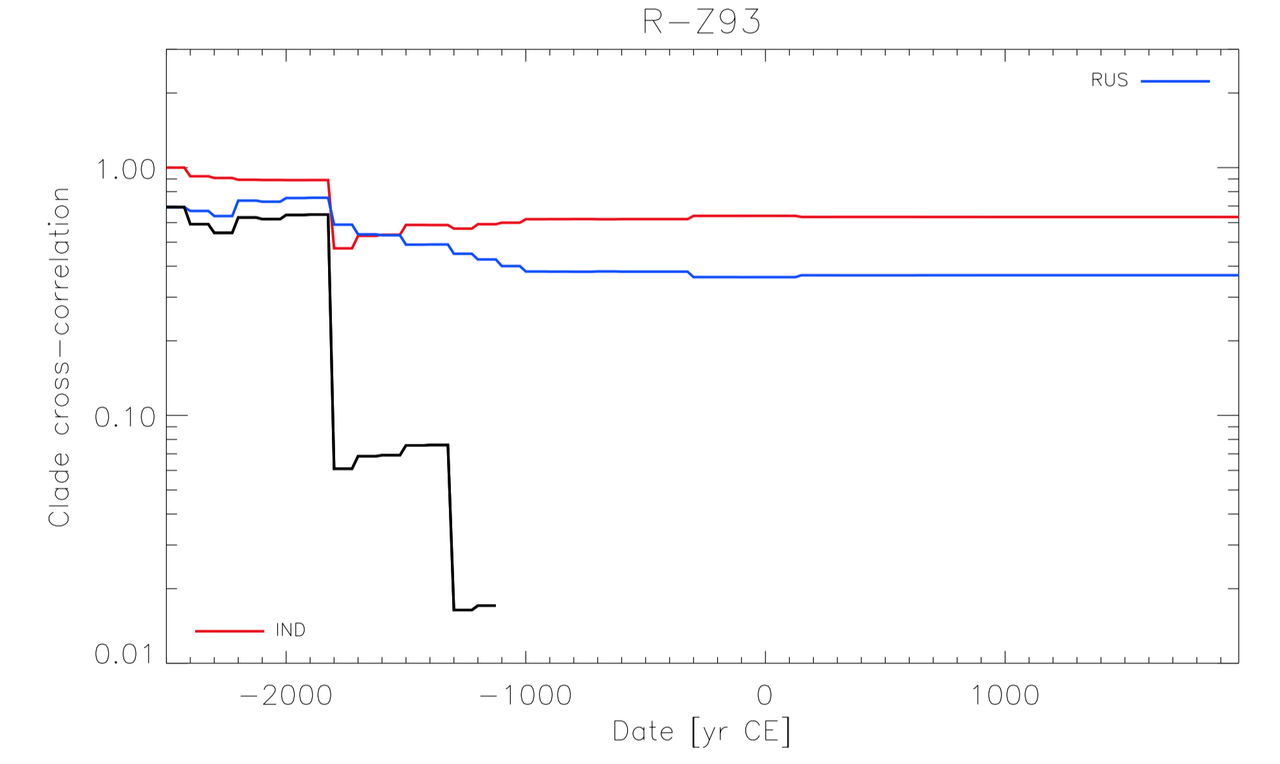

So the only three characters in (50) that ostensibly support a unique [Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic] node are all highlyproblematic, much debated in Indo-European linguistics, and not widely accepted as probative that the node didactually exist. Ringe himself warns that overall, even his preferred tree is supported by very few characters, andcontradicted by more: “18 characters are incompatible with the ‘best’ tree returned ... in computational terms ourresult is a total failure” (p. 85 in (50)). Ringe concedes that “the higher-order subgrouping of the lE family hasremained an unsolved problem for so many generations partly because the evidence is genuinely meagre” (p. 98 in(50)). In his own analysis, “the evidence for virtually all the larger, non-traditional subgroups that our algorithmposits is so slender” (p. 104 in (50)): no more than a handful of binary characters for any higher node. This is asreflected in the very low (>0.3) support values for the first three splits in our results here, and only 0.15 support for[Indo-Iranic + Balto-Slavic]. We take the linguistic data — qualitative as well as quantitative — as far fromsupporting such a node, especially not as the last major node to break up in the model for the Steppe hypothesis setout in (5), and when taken to have remained intact until less than a millennium before Vedic. We therefore alsotake it as premature for interpretations of aDNA data to presume the Ringe tree and its chronology as if in supportof a late presence of Indo-Iranic on the Steppe, before a late entry into India and Iran, in order to fit the Steppehypothesis.