Ancient West African foragers in the context of African population history

Abstract

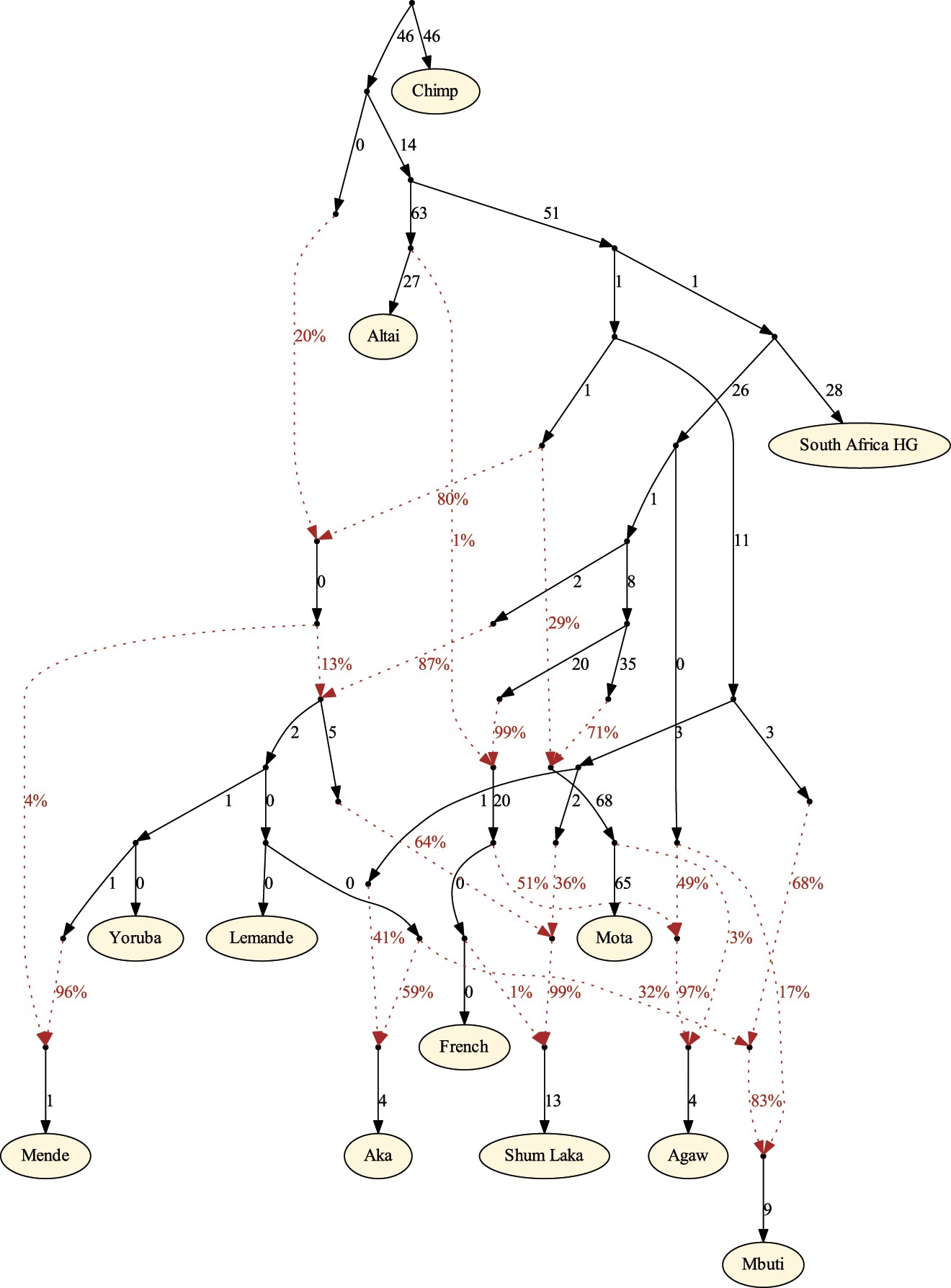

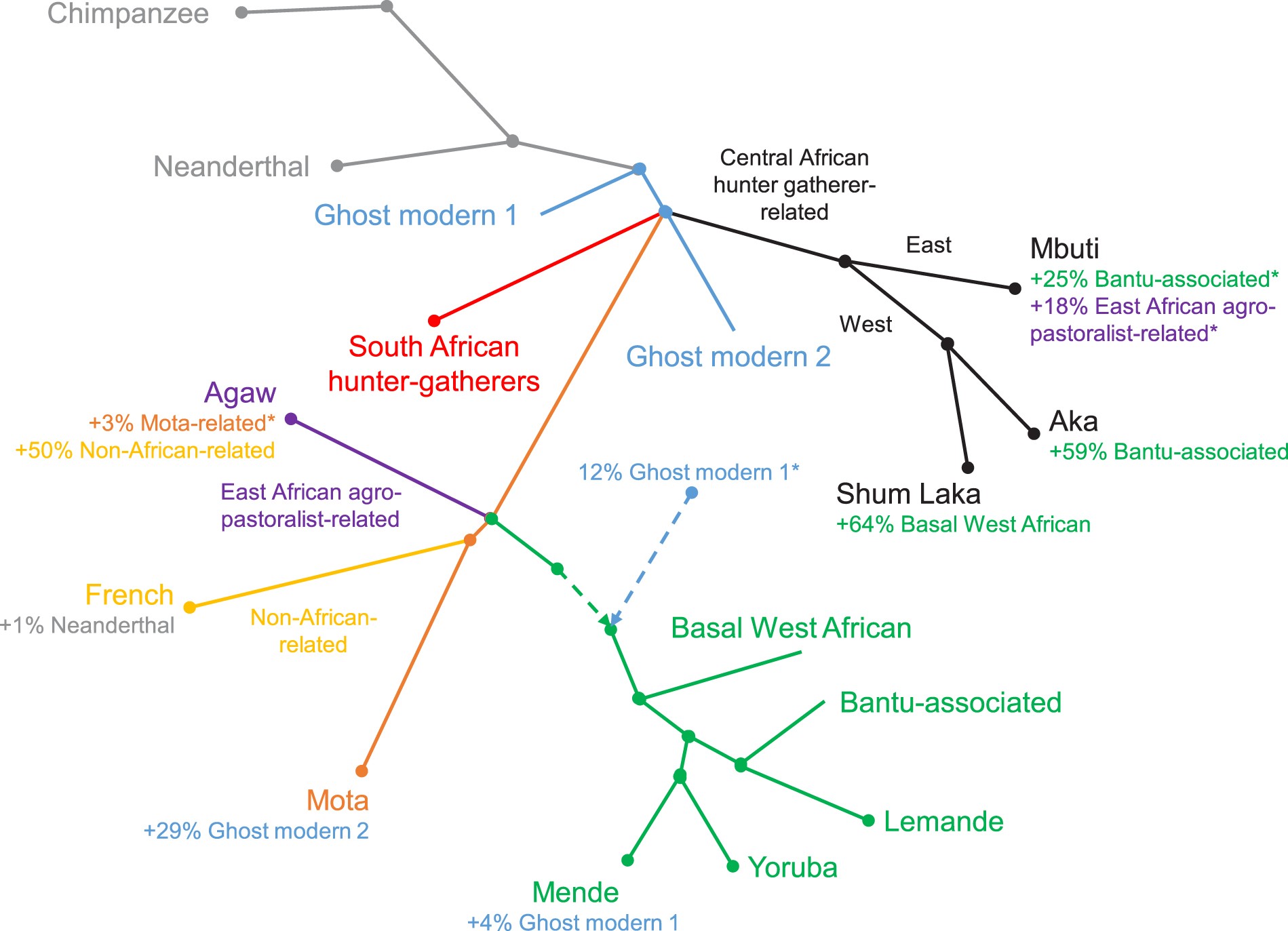

Our knowledge of ancient human population structure in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly prior to the advent of food production, remains limited. Here we report genome-wide DNA data from four children—two of whom were buried approximately 8,000 years ago and two 3,000 years ago—from Shum Laka (Cameroon), one of the earliest known archaeological sites within the probable homeland of the Bantu language group. One individual carried the deeply divergent Y chromosome haplogroup A00, which today is found almost exclusively in the same region. However, the genome-wide ancestry profiles of all four individuals are most similar to those of present-day hunter-gatherers from western Central Africa, which implies that populations in western Cameroon today—as well as speakers of Bantu languages from across the continent—are not descended substantially from the population represented by these four people. We infer an Africa-wide phylogeny that features widespread admixture and three prominent radiations, including one that gave rise to at least four major lineages deep in the history of modern humans.

The article is behind a paywall, but it has been explained in Nature News (Ancient African genomes offer glimpse into early human history) and in the New York Times (Ancient DNA from West Africa Adds to Picture of Humans’ Rise).

Here is the Supplementary information.

The study found that the genomes of the four Shum Laka children tested were remarkably similar despite the 5000 years gap between some of them.

The major surprise was that none of the people at Shum Laka were closely related to the Bantu speakers, even though the mainstream theory is that Proto-Bantu language originated in Cameroon between 1000 and 500 BCE. The four skeletons analysed had a strong kinship to the Aka, a group of hunter-gatherers with a pygmy body type who live today in rain forests 1,500 km to the east. It may simply be because the region was home to Proto-Bantu farmers as well as Shum Laka-like hunter-gatherers and that the samples analysed happened to belong to the latter.

Abstract

Our knowledge of ancient human population structure in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly prior to the advent of food production, remains limited. Here we report genome-wide DNA data from four children—two of whom were buried approximately 8,000 years ago and two 3,000 years ago—from Shum Laka (Cameroon), one of the earliest known archaeological sites within the probable homeland of the Bantu language group. One individual carried the deeply divergent Y chromosome haplogroup A00, which today is found almost exclusively in the same region. However, the genome-wide ancestry profiles of all four individuals are most similar to those of present-day hunter-gatherers from western Central Africa, which implies that populations in western Cameroon today—as well as speakers of Bantu languages from across the continent—are not descended substantially from the population represented by these four people. We infer an Africa-wide phylogeny that features widespread admixture and three prominent radiations, including one that gave rise to at least four major lineages deep in the history of modern humans.

The article is behind a paywall, but it has been explained in Nature News (Ancient African genomes offer glimpse into early human history) and in the New York Times (Ancient DNA from West Africa Adds to Picture of Humans’ Rise).

Here is the Supplementary information.

The study found that the genomes of the four Shum Laka children tested were remarkably similar despite the 5000 years gap between some of them.

The major surprise was that none of the people at Shum Laka were closely related to the Bantu speakers, even though the mainstream theory is that Proto-Bantu language originated in Cameroon between 1000 and 500 BCE. The four skeletons analysed had a strong kinship to the Aka, a group of hunter-gatherers with a pygmy body type who live today in rain forests 1,500 km to the east. It may simply be because the region was home to Proto-Bantu farmers as well as Shum Laka-like hunter-gatherers and that the samples analysed happened to belong to the latter.