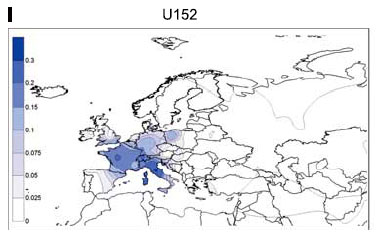

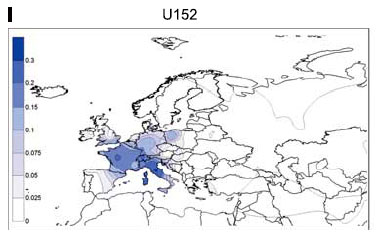

The last new paper by Myres et al. shed new light on the overall distribution of one of the principal branches of R1b, R-U152 (aka S28). It was already clear before that R-U152 was strong in the northern half of Italy, around the Alps, southern Germany, eastern France and Belgium. It now seems that U152 is common all over France, not just in the East. (see attached map)

Interestingly its presence in Iberia is mostly confined to Catalonia. In England it is almost exclusively found in the south, where it can exceeds 10% of the lineages.

It was obvious before that U152 was virtually absent of northern Germany, Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. But a sizeable pocket has been found in western Poland.

The last noteworthy observation is that U152 is very strong in both Corsica and Sardinia.

I have so far supported that R1b1b2a1 represents the Italo-Celto-Germanic people, i.e. the branch of the Indo-European speakers from the Pontic steppe that settled in Central Europe and dispersed all over Western and Northern Europe. In this theory, R-U106/S21 represents the Germanic branch, and R-P312/S116 the Italo-Celtic branch.

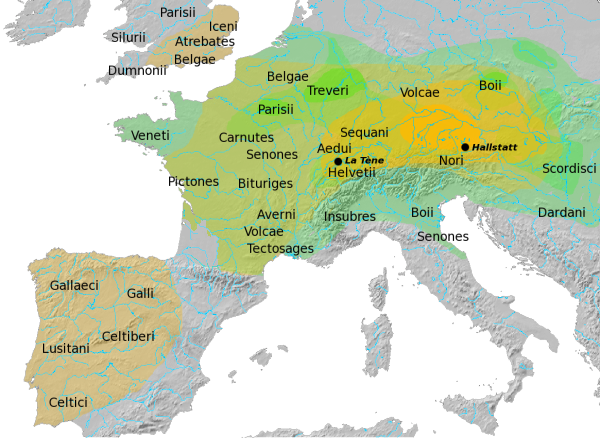

As such U152 is a branch of Italo-Celtic. But does it represent more accurately the Italic branch alone, or not ? In the last two and a half years I have equated U152 with the Alpine Celts, and more specifically the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures, that radiated from southern Germany to northern Italy, France, Belgium and southern England. If you compare the map of U152 with that of the Hallstatt/La Tène culture, the correlation is evident.

The only areas that don't match are north-western Iberia and Italy.

North-western Iberia was part of the La Tène culture, but only has a low percentage of U152. This can be explained simply: a small group of La Tne Celts migrated to N-E Iberia and exported their culture there while being genetically absorbed by the locals (other Celts).

But what about Italy ? If U152 was indeed associated with Hallstatt and La Tène Celts, why is it so common in the Italian peninsula ?

1) The first possibility is that Celts moved in great number to Italy. This has been historically documented by the migration of the Gauls to northern Italy, which the Romans renamed Gallia Cisalpina. Just after the Roman conquest of Gaul and southern Germany, hundreds of thousands of Gauls were taken as slaves to Italy. In the following centuries, as they became integrated in Roman society, many more Gauls moved to Italy for business or politics. It is also documented that numerous Roman senators were of Gaulish origin. Once they have reached the top level in government, it is easy to imagine that just anybody from Gaul could settle in Italy (and vice-versa, as countless Romans established themselves in Gaul).

This is all very well, but it doesn't really explain why R-152 is so strong in Corsica and Sardinia. These islands were not settled by any migrating Celts that I know of, and their remoteness and little political or economic importance did not make them prime destinations for Gauls to settle in.

Additionally, Myres' map shows that U152 peaks around Umbria and the Latium but is weaker in Alpine Italy. This could be because Gauls migrated en masse to Rome, or because so many of them were taken as slaves to Rome. But it could just as well be because U152 was actually Roman to start with.

2) This leads us to the second hypothesis: Italic people were an early offshoot of the Hallstatt Celts, and therefore all Italic tribes, including the Romans, carried a high percentage of U152. The migration to Italy might have happened at the beginning of the Hallstatt period (circa 1200-1000 BCE), or just before, during the Tumulus culture (see maps).

I think that the answer is surely a combination of both hypothesis. U152 has numerous subclades, and some might later be identified as Roman, or at least Italic, while others will be exclusively Gaulish or North Alpine. So far data is too scarce to see any pattern. The main subclade of U152 is L2, which is found in roughly 3/4 of all lineages, but indiscriminately anywhere from Italy to England.

Interestingly its presence in Iberia is mostly confined to Catalonia. In England it is almost exclusively found in the south, where it can exceeds 10% of the lineages.

It was obvious before that U152 was virtually absent of northern Germany, Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. But a sizeable pocket has been found in western Poland.

The last noteworthy observation is that U152 is very strong in both Corsica and Sardinia.

I have so far supported that R1b1b2a1 represents the Italo-Celto-Germanic people, i.e. the branch of the Indo-European speakers from the Pontic steppe that settled in Central Europe and dispersed all over Western and Northern Europe. In this theory, R-U106/S21 represents the Germanic branch, and R-P312/S116 the Italo-Celtic branch.

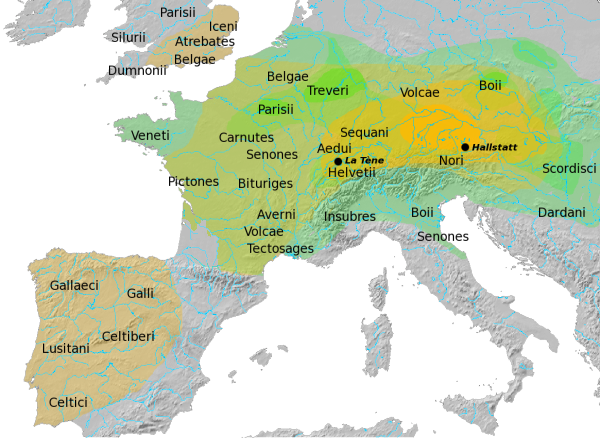

As such U152 is a branch of Italo-Celtic. But does it represent more accurately the Italic branch alone, or not ? In the last two and a half years I have equated U152 with the Alpine Celts, and more specifically the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures, that radiated from southern Germany to northern Italy, France, Belgium and southern England. If you compare the map of U152 with that of the Hallstatt/La Tène culture, the correlation is evident.

The only areas that don't match are north-western Iberia and Italy.

North-western Iberia was part of the La Tène culture, but only has a low percentage of U152. This can be explained simply: a small group of La Tne Celts migrated to N-E Iberia and exported their culture there while being genetically absorbed by the locals (other Celts).

But what about Italy ? If U152 was indeed associated with Hallstatt and La Tène Celts, why is it so common in the Italian peninsula ?

1) The first possibility is that Celts moved in great number to Italy. This has been historically documented by the migration of the Gauls to northern Italy, which the Romans renamed Gallia Cisalpina. Just after the Roman conquest of Gaul and southern Germany, hundreds of thousands of Gauls were taken as slaves to Italy. In the following centuries, as they became integrated in Roman society, many more Gauls moved to Italy for business or politics. It is also documented that numerous Roman senators were of Gaulish origin. Once they have reached the top level in government, it is easy to imagine that just anybody from Gaul could settle in Italy (and vice-versa, as countless Romans established themselves in Gaul).

This is all very well, but it doesn't really explain why R-152 is so strong in Corsica and Sardinia. These islands were not settled by any migrating Celts that I know of, and their remoteness and little political or economic importance did not make them prime destinations for Gauls to settle in.

Additionally, Myres' map shows that U152 peaks around Umbria and the Latium but is weaker in Alpine Italy. This could be because Gauls migrated en masse to Rome, or because so many of them were taken as slaves to Rome. But it could just as well be because U152 was actually Roman to start with.

2) This leads us to the second hypothesis: Italic people were an early offshoot of the Hallstatt Celts, and therefore all Italic tribes, including the Romans, carried a high percentage of U152. The migration to Italy might have happened at the beginning of the Hallstatt period (circa 1200-1000 BCE), or just before, during the Tumulus culture (see maps).

I think that the answer is surely a combination of both hypothesis. U152 has numerous subclades, and some might later be identified as Roman, or at least Italic, while others will be exclusively Gaulish or North Alpine. So far data is too scarce to see any pattern. The main subclade of U152 is L2, which is found in roughly 3/4 of all lineages, but indiscriminately anywhere from Italy to England.