23andMe : New Research on FOXP2 Gene in Mice Reveals Insights to Origins of Language in Humans

Mice are geneticists' best friends in the lab. The mouse genome is 75% identical to the human genome. They breed and mature very quickly, which makes of them very convenient candidates for genetic experiments. Disease causing mutations in mice and humans are usually the same, so that understanding how genes work in mice help a lot understanding our own DNA. Even phenotypical mutations, such as those responsible for eye or hair colour, show strong similarity between humans and our rodent cousins.

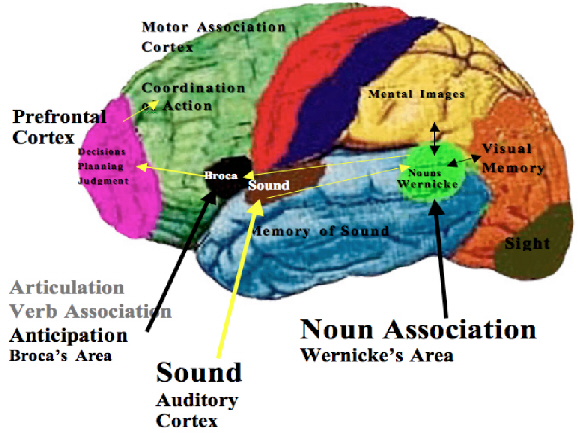

The human variant of the FOXP2 gene, thought to be responsible for speech, has been inserted in mice. The results are stunning. Although mice do not have the required vocal chords to speak like us, their brain circuitry and communication patterns were altered significantly.

Whales and dolphins could also possess complex language with a grammatical structure. I wonder how their version of FOXP2 compares with humans and other mammals.

Neanderthals had the same version of FOXP2 as us (which Homo Sapiens may have inherited from Neanderthal at one point or another or vice versa), but chimps do not. Would a genetically modified chimp with a human FOXP2 be able to produce human-like speech ? This will require an experiment.

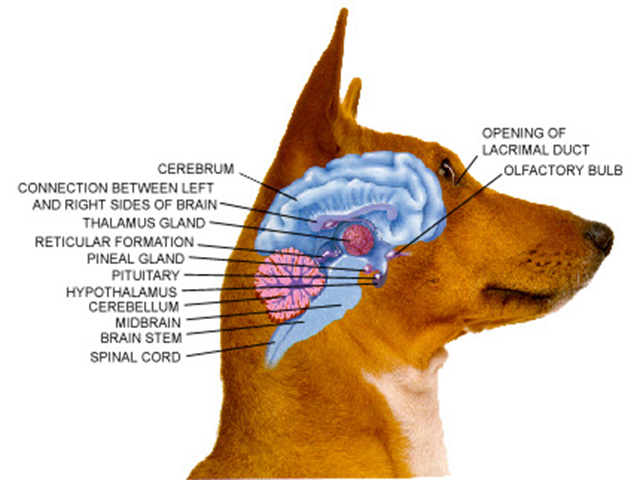

In any case, the experiment on mice confirms that humans aren't that different from other mammals. If several genes are successfully modified in mice (adapting the vocal chords for speech and increasing a bit brain size in the speech region) we might well have talking mice in the future (although very limited in their vocabulary due to their brain size, so it won't be much more than the present chirps adapted to sound more recognisable/intelligible to human ears). Who knows, if this tendency spreads that could allow us to communicate better with our pets.

Mice are geneticists' best friends in the lab. The mouse genome is 75% identical to the human genome. They breed and mature very quickly, which makes of them very convenient candidates for genetic experiments. Disease causing mutations in mice and humans are usually the same, so that understanding how genes work in mice help a lot understanding our own DNA. Even phenotypical mutations, such as those responsible for eye or hair colour, show strong similarity between humans and our rodent cousins.

The human variant of the FOXP2 gene, thought to be responsible for speech, has been inserted in mice. The results are stunning. Although mice do not have the required vocal chords to speak like us, their brain circuitry and communication patterns were altered significantly.

Whales and dolphins could also possess complex language with a grammatical structure. I wonder how their version of FOXP2 compares with humans and other mammals.

Neanderthals had the same version of FOXP2 as us (which Homo Sapiens may have inherited from Neanderthal at one point or another or vice versa), but chimps do not. Would a genetically modified chimp with a human FOXP2 be able to produce human-like speech ? This will require an experiment.

In any case, the experiment on mice confirms that humans aren't that different from other mammals. If several genes are successfully modified in mice (adapting the vocal chords for speech and increasing a bit brain size in the speech region) we might well have talking mice in the future (although very limited in their vocabulary due to their brain size, so it won't be much more than the present chirps adapted to sound more recognisable/intelligible to human ears). Who knows, if this tendency spreads that could allow us to communicate better with our pets.