Sile

Banned

- Messages

- 5,110

- Reaction score

- 582

- Points

- 0

- Location

- Australia

- Ethnic group

- North Alpine Italian

- Y-DNA haplogroup

- T1a2 -Z19945..Jura

- mtDNA haplogroup

- H95a1 ..Pannoni

I'm not familiar with this theory. I have read that the emergence of the Zarubintsy culture is associated with an eastward migration of people belonging to the Pomeranian culture into territory occupied by people of the Milograd culture, and the subsequent mixture between those cultures, which lasted for quite a long time (W. W. Siedow, Седов В. В., Славяние верхнево Поднепровья и Подвинья). The Zarubintsy culture is considered by some scholars Proto-Slavic as it seems to correspond with archaic Slavic hydronymy (Третьяков П. Н., Памятники зарубинецкой культуры). Milograd culture is considered by many scholars Balto-Slavic (before its differentiation into Proto-Slavic, West Baltic and East Baltic) or West Baltic, but Siedow wrote: "В лингвистической литературе высказывались предположения о формировании праславянского на основе одного из окраинных западнобалтийских диалектов или, наоборот, о происхождении западнобалтийских диалектов от одной из групп праславянских говоров." Also Bernstein wrote: "Нет сомнения в том, что балто-славянская сообщность охватила прежде всего праславянский, прусский, ятвяжский язык". So Proto-Slavic and West-Baltic were more closely related than was Proto-Slavic with East Baltic (let's remind you that according to more recent theories, there was no such a thing as a unified Baltic, which later splint into West Baltic and East Baltic - but there was Balto-Slavic which split directly into three branches: West Baltic, Slavic and East Baltic). By the end of the 1st century AD the Zarubintsy culture - according to Siedow - was conquered by Sarmatians, but part of their population escaped northward as refugees and settled in Prussia (archaeological prove of this are supposed to be the type of fibulae which had been previously produced by the Zarubintsy culture, and which start to appear in Prussia in the 2nd century AD). Before that, the Lusatian culture fell to Scythians (see page 76 here: http://www.parzifal-ev.de/uploads/media/gimbutas.pdf), so most likely the Pomeranian culture - which evolved out of the Lusatian culture (see below) had some Scythian admixture as well.

https://archive.org/details/TheBalts

If we add also your info about contribution of Gubin culture (I guess it contributed more to southern part of that culture than to its northern part), then we have a picture of Proto-Slavs emerging from a mixture of the following archaeological cultures: Milograd (West Balts? or Balto-Slavs?), Pomeranian ("Lusatian" - whoever those Lusatians were - mixed with Scythians) and Gubin (Germano-Celtic Bastarnae?). This would mean that those four peoples contributed to the ethnogenesis of Slavs. So they would be ancestors of Slavs, not some later addition to Slavs. So even if Bastarnae (or maybe Celts who influenced them) originally carried I2a-Din, then still it was part of Slavs since the beginning of their ethnogenesis. A later addition to Slavs - on the other hand - would be Sarmatians, to which the Zarubintsy culture fell by the end of the 1st century AD (according to Siedow). When it comes to the Pomeranian culture:

But it evolved as the result of Scythian influence on the Lusatian culture (see Marija Gimbutas in the link above).

The study by Haak et. al. 2015 found R1a Z280 in an individual of the Lusatian culture from Halberstadt in Germany.

I quoted all the details about that Z280 individual here (what is interesting, that guy was probably a redhead):

http://www.eupedia.com/forum/thread...istoric-Europe?p=451553&viewfull=1#post451553

R1a Z280 is today present in all Slavic and Baltic populations in frequencies between ca. 10% and ca. 50% of all males.

================

All of this suggests that Proto-Slavs evolved out of an interesting mix of Balts (or Balto-Slavs as they are also called - but Balto-Slavic language was rather more similar to modern Baltic languages than to modern Slavic), Lusatians (maybe they spoke some unknown Indo-European language - Venedic, if such a language existed - some scholars hypothesize the existence of Venedic languages as yet another branch of IE), the Bastarnae or Peucini (Germano-Celtic), Scythians and - the final addition - Sarmatians.

I am probably starting to sound like Germanophiles who see "Germanicness" everywhere. :grin:

================

As for the Balto-Slavic past. There are several theories about this:

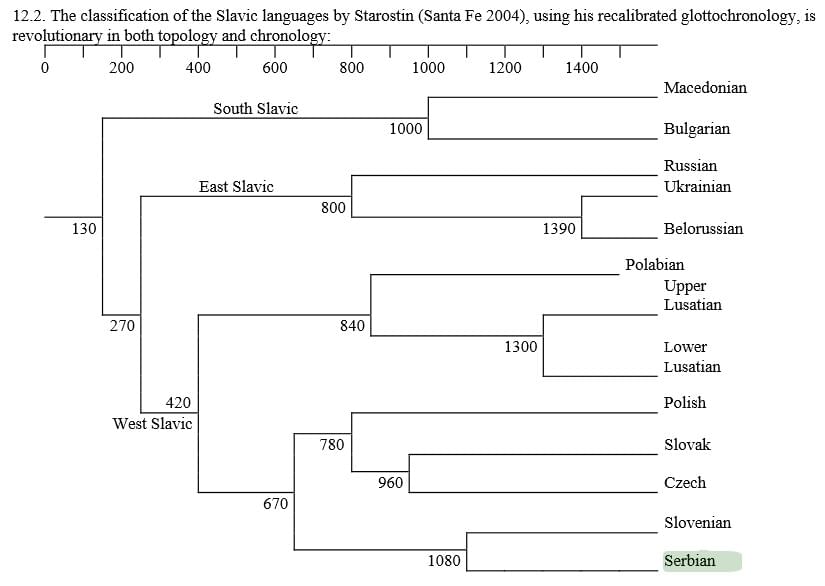

The graph illustrates several models of Balto-Slavic interactions, trying to explain similarities between the two groups (Schleicher - common ancestral language separating into Baltic and Slavic; Endzelins - two separate languages which came under influence of each other at some point; Rozwadowski - common ancestry, then separation, followed by becoming close neighbours again; Meillet - prolonged close influences despite lack of common ancestry; Kromer - common ancestry with Baltia never constituting a linguistic unity, but East Baltic and West Baltic groups separating directly from Balto-Slavic). Rozwadowski's model is also interesting.

Currently the mostly commonly accepted model when it comes to differentiation of Baltic is this first suggested by Kromer in 2003 - namely that there was no unified Baltic language (from which later West Baltic and East Baltic emerged), but that Balto-Slavic (which, however, was more similar to Baltic than to Slavic) split directly into three parts - West Baltic (now extinct), Slavic and East Baltic.

Here the theories of Schleicher and Endzelins are outlined:

There is also no perfect agreement on when did the separation of Slavic and Baltic (or both Baltic groups) take place.

Proposed dates range from ca. 1500 BCE to ca. 500 BCE (3500 - 2500 years ago):

Atkinson - 1400 BCE

Novotná & Blažek - 1400–1340 BCE

Sergei Starostin - 1210 BCE

Chang et. al. - 600 BCE (http://www.linguisticsociety.org/files/news/ChangEtAlPreprint.pdf)

===============================

Or maybe something like this:

Except that I2 is Non-Indo-European and Germanic people are Indo-European (despite Non-IE admixtures).

So it can only be Pre-Germanic rather than Germnaic. Or it can be Pre-Slavic.

I1 is also Pre-Germanic (it was probably absorbed by Proto-Germanic Indo-Europeans from LBK culture).

https://www.academia.edu/4835555/Gallo-Scythians

referred as Bastanae

https://www.academia.edu/4118437/Mediolana_and_the_Zaravetz_Culture

[h=2]Who Were The Bastarnae ?[/h] Filed under: Archaeology, History, Numismatics — 1 Comment

March 26, 2014

‘…the Bastarnæ, the bravest nation of all’.

(Appianus, Mithridatic Wars 10:69)

The most enigmatic ‘barbarian’ people to appear in southeastern Europe in the late Iron Age are undoubtedly the Bastarnae (Βαστάρναι / Βαστέρναι).

While archaeological/numismatic evidence indicates that the Bastarnae tribes had reached the Danube Delta as early as the second half of the 4th c. BC, they first appear in historical sources in connection with the events of 179 BC as allies of Philip V of Macedonia in his war with Rome (Livy 40:5, 57-58), and remain a constant factor in the history of southeastern Europe for over 500 years. Due to the fact that archaeologists have failed to associate a particular archaeological culture with the Bastarnae, the ethnic origin of this people has hitherto remained shrouded in mystery, with a lack of clarity on whether they were initially of Scythian, Germanic or Celtic origin. However, as illustrated below, a chronological analysis of the ancient sources relating to the Bastarnae in general, and archaeological, numismatic and linguistic evidence from the territory of the Bastarnae Peucini tribe in particular, enables us to finally shed some light on this question.

Bastarnae ‘Huşi-Vovrieşti type’ tetradrachms from the Celtic settlement at Pelczyska, Poland (2nd c. BC)

(see Balkancelts ‘The Celts in Poland’ article)

THE SOURCES

Later authors such as Dio Cassius (3rd c. AD – Dio LI.23.3, 24.2) and Zosimus (late 5th/early 6th c. AD – Zosimus I.34) define the Bastarnae as ‘Scythians’, and to a great extent this is true. By the late Roman period the Bastarnae tribes had been living in the region vaguely referred to as ‘Scythia’ for over half a millennium, and mixing with the local tribes (‘mixed marriages are giving them to some extent the vile appearance of the Sarmatians’ – Tac. Ger. 46). Thus, they were by this stage indeed Scythians, in the same way, for example, the Celtic Scordisci in Thrace are referred to in Roman sources as ‘Thracians’, having inhabited the region of Thrace for a number of centuries. However, as with the latter case, geographical situation by no means indicates ethnic origin.

Facial Reconstruction of a Bastarnae woman found in Burial # 9 at the Celtic settlement in Pelczyska, Poland

(see Balkancelts ‘Face of a Stranger’ article’)

While sources such as Strabo (early 1st c. AD – see below), and Tacitus (circa 100 AD; Tac. Ger. 43), are often cited to support the view that the Bastarnae were of Germanic origin, in fact, a closer analysis of the testimony of both these sources reveals that neither is in fact certain about who the Bastarnae were. While Strabo informs us that the Bastarnae lived mixed with the Thracian and Celtic tribes in Thrace, both north and south of the river, he also admits, ‘I know neither the Bastarnae, nor the Sarmatae nor, in a word, any of the peoples who dwell above the Pontus’ (Strabo VII, 2:4). Tacitus states the following:

‘Peucini, quos quidam Bastarnas, vocunt sermon cultu, sede ac domiciliis ut Germani agunt’ (Tac. op cit.)

i.e. – he informs us, not that the Bastarnae were Germani, but that they were ‘similar to the Germani’. In this case one should bear in mind that many of the Celts who migrated into southeastern Europe and Asia-Minor from the end of the 4th c. BC onwards originated from the Belgae group of Celtic tribes (see also ‘Galatia’ article), who are described in ancient sources as being most like the Germani.

The other ancient authors are clear on the ethnic origin of the Bastarnae. The earliest source, Polybius (200-118 BC; XXIV 9,13) refers to them as Celtic (Galatians), while Livy (59 BC – 17 AD) tells us that they had the same customs and spoke the same language as the Celtic Scordisci, and also mentions close military and political ties between the Bastarnae and Scordisci (Livy 40:57). Plutarch (46 – 120 AD; Aem. 9.6) refers to them as ‘Gauls on the Danube who are called Bastarnae’.

THE BASTARNAE IN THRACE

It was in the wake of the aforementioned events of 179 BC that the Peucini, the southern branch of the Bastarnae, were drawn south of the Danube into Thrace. They were at this stage a powerful military and political force in southeastern Europe, which is illustrated by the enthusiasm that Philip V of Macedonia showed at the prospect of being allied to them:

‘The envoys whom he had sent to the Bastarnae to summon assistance had returned and brought back with them some young nobles, amongst them some of royal blood. One of these promised to give his sister in marriage to Philip’s son, and the king was quite elated at the prospect of an alliance with that nation’ (Livy 40:5).

Although Philip’s sudden death meant that the joint attack on Rome by the Macedonians and Bastarnae came to nothing, by this time a large group of the (Peucini) Bastarnae had already migrated into Thrace, and a group of 30,000 of them subsequently settled in Dardania; another larger group of Bastarnae returned eastwards and settled in the area of today’s eastern Bulgaria (Livy 40:58), where Bastarnae kingdoms were established in the Dobruja area. At the beginning of the 1st c. AD Strabo (VII, 3:2) mentions that the ethnic make-up of this area consisted of a complex mix of Thracians, Scythians, Celts and Bastarnae:

“the Bastarnae tribes are mingled with the Thracians, more indeed with those beyond the Ister (Danube), but also with those this side. And mingled with them are also the Celtic tribes…”.

A thriving ‘barbarian’ culture emerged in this area (southeastern Romania/northeastern Bulgaria) during the 2nd/ 1st c. BC, based on a symbiotic relationship between these various groups and the Greek Black Sea colonies – a culture which was brought to a brutal end in the mid 1st c. BC by the destructive rampage of the Getic leader Burebista, which also paved the way for the Roman conquest of the Dobruja.

Bronze issue of the (Peucini) Bastarnae king Aelis (s. Dobruja region, Bulgaria – c. 180-150 BC).

- Jugate heads of the Dioskouroi right, in wreathed caps / jugate horse heads right; monogram & ΠΕ (for Peucini) below

(see also ‘Balkancelts ‘Peucini’ article)

In summary, an analysis of the ancient sources would appear to indicate that the Bastarnae tribes were initially of Celtic (Belgic) origin. This is confirmed by numismatic, archaeological, and linguistic evidence from the territory of the Bastarnae Peucini tribe in n.e. Bulgaria, s.e. Romania, Moldova and Ukraine. One should also note that the first archaeological/numismatic evidence of the presence of the Bastarnae in s.e. Europe (2nd half of the 4th c. BC) corresponds chronologically with the Celtic migration into the region.

It would therefore appear, based on the available scientific data, that the elusive Bastarnae tribes were not some mysterious Germanic people who appeared in southeastern Europe during this period, but that they, like the Galatians, were tribes of the Belgae group who migrated into the area during the Celtic expansion at the end of the 4th / beginning of the 3rd c. BC. Scientific evidence from the Dobruja region (loc cit) further indicates that the original Celto-Germanic (Belgic) nature of this culture subsequently underwent a fundamental metamorphosis due to prolonged contact and co-existence with the Hellenistic and Scythian cultures, the resulting fusion of Celtic, Hellenistic and Scythian cultural elements culminating in a unique and distinct Bastarnae ethnicity by the Roman period.

In the later Roman period the policy of ethnic engineering further strengthened the Bastarnae presence south of the Danube. Under the Emperor Probus (276-82) 100,000 of them were settled in Thrace (Historia Augusta Probus 18), and shortly afterwards Emperor Diocletian (284-305) carried out another ‘massive’ transfer of the Bastarnae population to the south of the Danube (Eutropius IX.25; see Balkancelts ‘Ethnic Engineering’ article). Thus, the Bastarnae presence on the territory of today’s Bulgaria, already well established since the 2nd c. BC, was further reinforced by the policies of both Probus and Diocletian.