Syd

Regular Member

- Messages

- 46

- Reaction score

- 31

- Points

- 18

- Location

- Italy

- Ethnic group

- Latin

- Y-DNA haplogroup

- R-DF13*

- mtDNA haplogroup

- H

A multidisciplinary study on human- Animal co- burials from the Late Iron Age necropolis of Seminario Vescovile in Verona (Northern Italy, 3rd-1st c. BCE).

Abstract

Animal remains are a common find in prehistoric and protohistoric funerary contexts. While taphonomic and osteological data provide insights about the proximate (depositional) factors responsible for these findings, the ultimate cultural causes leading to this observed mortuary behavior are obscured by the opacity of the archaeological record and the lack of written sources. Here, we apply an interdisciplinary suite of analytical approaches (zooarchaeological, anthropological, archaeological, paleogenetic, and isotopic) to explore the funerary deposition of animal remains and the nature of joint human-animal burials at Seminario Vescovile (Verona, Northern Italy 3rd-1st c. BCE). This context, culturally attributed to the Cenomane culture, features 161 inhumations, of which only 16 included animal remains in the form of full skeletons, isolated skeletal parts, or food offerings. Of these, four are of particular interest as they contain either horses (Equus caballus) or dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)–animals that did not play a dietary role. Analyses show no demographic, dietary, funerary similarities, or genetic relatedness between individuals buried with animals. Isotopic data from two analyzed dogs suggest differing management strategies for these animals, possibly linked to economic and/or ritual factors. Overall, our results point to the unsuitability of simple, straightforward explanations for the observed funerary variability. At the same time, they connect the evidence from Seminario Vescovile with documented Transalpine cultural traditions possibly influenced by local and Roman customs.

Human ancient DNA analysis

We collected bone powder from the inner part of the Pars Petrosa (PP) [77] of the human individuals buried with animals (n = 16). This step was carried out in a dedicated pre-PCR area of the ancient DNA (aDNA) laboratory of Eurac Research in Bolzano (Italy). Double-stranded genomic libraries were constructed [78] and sent to an external company (Macrogen Sequencing Centre, Seoul) for shotgun sequencing. Through bioinformatic analyses of sequenced reads, we assessed the authenticity and preservation of the aDNA of the samples. Even though all samples comply with the quality criteria for the performance of the enrichment reaction (human endogenous content > 1%), we randomly selected 11 samples for the enrichment of more than 1.3 million SNPs on the human genome [79, 80] and subjected them to sequencing and additional bioinformatic analyses to assess the authenticity of aDNA reads [81] (see S1 Text for more details). Contamination estimates were then performed on mtDNA and X-chromosome data [82, 83] whose thresholds were set to 5% and 3% respectively. The genetic sex was determined using shotgun data only and merged data (shotgun + capture) (see S3 Table). We used two different methods [84, 85] following the required minimum number of human reads of 1,000 and 100,000, to obtain a reliable estimation for [84, 85], respectively. Moreover, we inferred biological relatedness among individuals using three different methods: TKGWV2, READ, and KIN [86–88] (see S1 Text for details). For all methods, we followed the thresholds suggested by the authors: for the READ method, a threshold of 0.1X mean coverage of the reads mapping to the human reference genome [87], for the TKGWV2 method, the threshold of 0.026X average coverage along with 18,000 SNPs [86], and for the KIN method, the threshold of 0.5 X sequence coverage [88].

Human ancient DNA

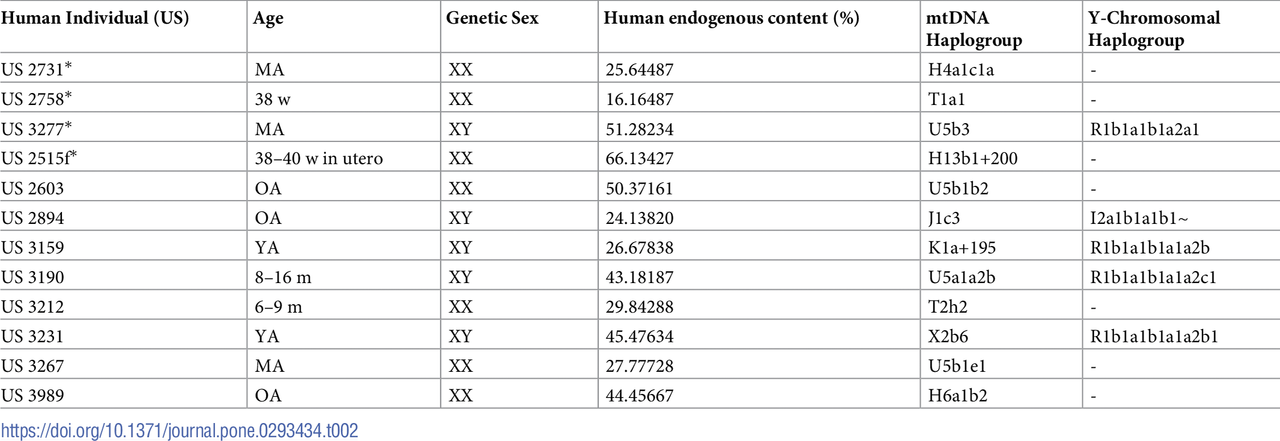

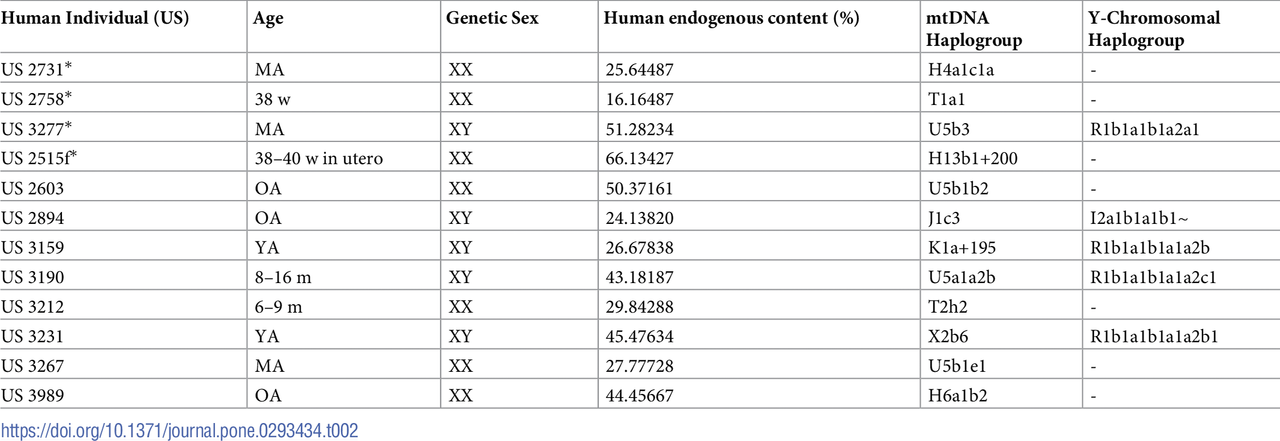

Paleogenetic analyses of the human samples from SV were performed on 15 of the 16 individuals associated with animal remains, either as a co-burial or as a food offering (Table 2). The perinatal individual from B18 was excluded due to extremely poor bone preservation (cf. S1 Table). Three individuals (US 3948, US 3251, and US 3178, each of whom had food offerings) were successively excluded from downstream analyses as the genomic data retrieved did not meet our quality criteria. The remaining twelve individuals showed preservation of endogenous DNA (shotgun + enrichment) ranging from 16.16% to 66.13% and mean coverage of sequences mapping to the human reference genome between 0.17 X and 0.66 X. All samples show a typical damage pattern for aDNA (average deamination at 5´) (S1 Fig) and low contamination from modern human DNA at a nuclear (≤ 3%) and mtDNA (≤ 5%) level (see S2 and S3 Tables). The analyses revealed a total of 5 males (XY) and 7 females (XX) (S2 Table). Individuals US 2731, US 2758, and US 2515f were all confirmed to be females (XX) (see Table 2 and S4 Table). Moreover, the genetic analysis allowed us to rectify a morphological.

journals.plos.org

journals.plos.org

Abstract

Animal remains are a common find in prehistoric and protohistoric funerary contexts. While taphonomic and osteological data provide insights about the proximate (depositional) factors responsible for these findings, the ultimate cultural causes leading to this observed mortuary behavior are obscured by the opacity of the archaeological record and the lack of written sources. Here, we apply an interdisciplinary suite of analytical approaches (zooarchaeological, anthropological, archaeological, paleogenetic, and isotopic) to explore the funerary deposition of animal remains and the nature of joint human-animal burials at Seminario Vescovile (Verona, Northern Italy 3rd-1st c. BCE). This context, culturally attributed to the Cenomane culture, features 161 inhumations, of which only 16 included animal remains in the form of full skeletons, isolated skeletal parts, or food offerings. Of these, four are of particular interest as they contain either horses (Equus caballus) or dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)–animals that did not play a dietary role. Analyses show no demographic, dietary, funerary similarities, or genetic relatedness between individuals buried with animals. Isotopic data from two analyzed dogs suggest differing management strategies for these animals, possibly linked to economic and/or ritual factors. Overall, our results point to the unsuitability of simple, straightforward explanations for the observed funerary variability. At the same time, they connect the evidence from Seminario Vescovile with documented Transalpine cultural traditions possibly influenced by local and Roman customs.

Human ancient DNA analysis

We collected bone powder from the inner part of the Pars Petrosa (PP) [77] of the human individuals buried with animals (n = 16). This step was carried out in a dedicated pre-PCR area of the ancient DNA (aDNA) laboratory of Eurac Research in Bolzano (Italy). Double-stranded genomic libraries were constructed [78] and sent to an external company (Macrogen Sequencing Centre, Seoul) for shotgun sequencing. Through bioinformatic analyses of sequenced reads, we assessed the authenticity and preservation of the aDNA of the samples. Even though all samples comply with the quality criteria for the performance of the enrichment reaction (human endogenous content > 1%), we randomly selected 11 samples for the enrichment of more than 1.3 million SNPs on the human genome [79, 80] and subjected them to sequencing and additional bioinformatic analyses to assess the authenticity of aDNA reads [81] (see S1 Text for more details). Contamination estimates were then performed on mtDNA and X-chromosome data [82, 83] whose thresholds were set to 5% and 3% respectively. The genetic sex was determined using shotgun data only and merged data (shotgun + capture) (see S3 Table). We used two different methods [84, 85] following the required minimum number of human reads of 1,000 and 100,000, to obtain a reliable estimation for [84, 85], respectively. Moreover, we inferred biological relatedness among individuals using three different methods: TKGWV2, READ, and KIN [86–88] (see S1 Text for details). For all methods, we followed the thresholds suggested by the authors: for the READ method, a threshold of 0.1X mean coverage of the reads mapping to the human reference genome [87], for the TKGWV2 method, the threshold of 0.026X average coverage along with 18,000 SNPs [86], and for the KIN method, the threshold of 0.5 X sequence coverage [88].

Human ancient DNA

Paleogenetic analyses of the human samples from SV were performed on 15 of the 16 individuals associated with animal remains, either as a co-burial or as a food offering (Table 2). The perinatal individual from B18 was excluded due to extremely poor bone preservation (cf. S1 Table). Three individuals (US 3948, US 3251, and US 3178, each of whom had food offerings) were successively excluded from downstream analyses as the genomic data retrieved did not meet our quality criteria. The remaining twelve individuals showed preservation of endogenous DNA (shotgun + enrichment) ranging from 16.16% to 66.13% and mean coverage of sequences mapping to the human reference genome between 0.17 X and 0.66 X. All samples show a typical damage pattern for aDNA (average deamination at 5´) (S1 Fig) and low contamination from modern human DNA at a nuclear (≤ 3%) and mtDNA (≤ 5%) level (see S2 and S3 Tables). The analyses revealed a total of 5 males (XY) and 7 females (XX) (S2 Table). Individuals US 2731, US 2758, and US 2515f were all confirmed to be females (XX) (see Table 2 and S4 Table). Moreover, the genetic analysis allowed us to rectify a morphological.

"Until death do us part". A multidisciplinary study on human- Animal co- burials from the Late Iron Age necropolis of Seminario Vescovile in Verona (Northern Italy, 3rd-1st c. BCE)

Animal remains are a common find in prehistoric and protohistoric funerary contexts. While taphonomic and osteological data provide insights about the proximate (depositional) factors responsible for these findings, the ultimate cultural causes leading to this observed mortuary behavior are...