The question that bothers me 2 years now, after Lazarides papper.

is BMAC and Andronovo,

what exchanges of culture happened there, and when.

an extract of a bigger digest, if useful:

[...

In these graves at Gonur, associated with the early settlement of Gonur North, one horse was found. A brick-lined grave pit contained the contorted bodies of ten adult humans who were apparently killed in the grave itself, one of whom fell across a small funeral wagon with solid wooden wheels. The grave also contained a whole dog, a whole camel, and the decapitated body of a horse foal (the reverse of an Aryan horse sacrifice). This grave is thought to have been a sacrificial offering that accompanied a nearby “royal” tomb. The royal tomb contained funeral gifts that included a bronze image of a horse head, probably a pommel decoration on a wooden staff. Another horse head image appeared as a decoration on a crested copper axe of the BMAC type, unfortunately obtained on the art market and now housed in the Louvre. Finally, a BMAC-style seal probably looted from a BMAC cemetery in Bactria (Afghanistan) showed a man riding a galloping equid that looks very much like a horse (see

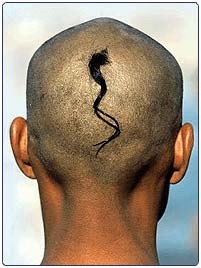

figure 16.3). The design was similar to the contemporary galloping-horse-and-rider image on the Ur III seal of Abbakalla, dated 2040–2050 BCE. Both seals showed a galloping horse, a rider with a hair-knot on the back of his head, and a man walking.

These finds suggest that horses began to appear in Central Asia about 2100–2000 BCE but never were used for food. They appeared only as decorative symbols on high-status objects and, in one case, in a funeral sacrifice. Given their simultaneous appearance across Iran and Mesopotamia, and the position of BMAC between the steppes and the southern civilizations, horses were probably a trade commodity. After chariots were introduced to the princes of the BMAC, Iran, and the Near East around 2000–1900 BCE, the demand for horses could easily have been on the order of tens of thousands of animals annually.

17

Steppe Immigrants in Central Asia

Fred Hiebert’s excavations at the walled town of Gonur North in Margiana, dated 2100–2000 BCE, turned up a few sherds of strange pottery, unlike any other pottery at Gonur. It was made with a paddle-and-anvil technique on a cloth-lined form—the clay was pounded over an upright cloth-covered pot to make the basic shape, and then was removed and finished. This is how Sintashta pottery was made. These strange sherds were imported from the steppe. At this stage (equivalent to early Sintashta) there was very little steppe pottery at Gonur, but it was there, at the same time a horse foal was thrown into a sacrificial pit in the Gonur North cemetery. Another possible trace of this early phase of contact were “Abashevo-like” pottery sherds decorated with horizontal channels, found at the tin miners’ camp at Karnab on the lower Zeravshan. Late Abashevo was contemporary with Sintashta.

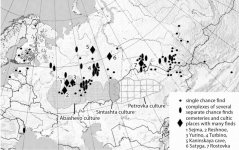

During the classic phase of the BMAC, 2000–1800 BCE, contact with steppe people became much more visible. Steppe pots were brought into the rural stronghold at Togolok 1 in Margiana, inside the larger palace/temple at Togolok 21, inside the central citadel at Gonur South, and inside the walled palace/temple at Djarkutan in Bactria (

figure 16.6). These sherds were clearly from steppe cultures. Similar designs can be found on Sintashta pots at Krivoe Ozero (k. 9, gr. 3; k. 10, gr. 13) but were more common on pottery of early Andronovo (Alakul variant) type, dated after 1900–1800 BCE—pottery like that used by the Andronovo miners at Karnab. Although the amount of steppe pottery in classic BMAC sites is small, it is widespread, and there is no doubt that it derived from northern steppe cultures. In these contexts, dated 2000–1800 BCE, the most likely steppe sources were the Petrovka culture at Tugai or the first Alakul-Andronovo tin miners at Karnab, both located in the Zeravshan valley.

18

The Petrovka settlement at Tugai appeared just 27 km downstream (west) of Sarazm, not far from the later site of Samarkand, the greatest caravan trading city of medieval Central Asia. Perhaps Tugai had a similar, if more modest, function in an early north-south trade network. The Petrovka culture (see below) was an eastern offshoot of Sintashta. The Petrovka people at Tugai constructed two copper-smelting ovens, crucibles with copper slag, and at least one dwelling. Their pottery included at least twenty-two pots made with the paddle-and-anvil technique on a cloth-lined form. Most of them were made of clay tempered with crushed shell, the standard mixture for Petrovka potters, but two were tempered with crushed talc/steatite minerals. Talc-tempered clays were typical of Sintashta, Abashevo, and even forest-zone pottery of Ural forager cultures, so these two pots probably were carried to the Zeravshan from the Ural steppes. The pottery shapes and impressed designs were classic early Petrovka (

figure 16.7). A substantial group of Petrovka people apparently moved from the Ural-Ishim steppes to Tugai, probably in wagons loaded with pottery and other possessions. They left garbage middens with the bones of cattle, sheep, and goats, but they did not eat horses—although their Petrovka relatives in the northern steppes did. Tugai also contained sherds of wheel-made cups in red-polished and black-polished fabrics typical of the latest phase at Sarazm (IV). The principal activity identified in the small excavated area was copper smelting.

19

Figure 16.6 A whole steppe pot found inside the walls of the Gonur South town, after Hiebert 1994; steppe sherds with zig-zag decoration found inside the walls of Togolok 1, after Kuzmina 2003; and similar motifs on Sintashta sherds from graves at Krivoe Ozero, Ural steppes, after Vinogradov 2003, figures 39 and 74.

Figure 16.7 The Petrovka settlement at Tugai on the Zeravshan River: (top) plan of excavation;

(center left) imported redware pottery like that of Sarazm IV;

(center right) two coarse ceramic crucibles from the metal-working area;

(bottom) Petrovka pottery. Adapted from Avanessova 1996.

The steppe immigrants at Tugai brought chariots with them. A grave at Zardcha-Khalifa 1 km east of Sarazm contained a male buried in a contracted pose on his right side, head to the northwest, in a large oval pit, 3.2 m by 2.1 m, with the skeleton of a ram.

20 The grave gifts included three wheel-made Namazga VI ceramic pots, typical of the wares made in Bactrian sites of the BMAC such as Sappali and Dzharkutan; a trough-spouted bronze vessel (typical of BMAC) and fragments of two others; a pair of gold trumpet-shaped earrings; a gold button; a bronze straight-pin with a small cast horse on one end; a stone pestle; two bronze bar bits with looped ends; and two largely complete bone disc-shaped cheekpieces of the Sintashta type, with fragments of two others (

figure 16.8). The two bronze bar bits are the oldest known metal bits anywhere. With the four cheekpieces they suggest equipment for a chariot team. The cheekpieces were a specific Sintashta type (the raised bump around the central hole is the key typological detail), though disc-shaped studded cheekpieces also appeared in many Petrovka graves. Stone pestles also frequently appeared in Sintashta and Petrovka graves. The Zardcha-Khalifa grave probably was that of an immigrant from the north who had acquired many BMAC luxury objects. He was buried with the only known BMAC-made pin with the figure of a horse—perhaps made just for him. The Zardcha-Khalifa chief may have been a horse dealer. The Zeravshan valley and the Ferghana valley just to the north might have become the breeding ground at this time for the fine horses for which they were known in later antiquity.

The fabric-impressed pottery and the sacrificed horse foal at Gonur North and perhaps the Abashevo (?) sherds at Karnab represent the exploratory phase of contact and trade between the northern steppes and the southern urban civilizations about 2100–2000 BCE, during the period when the kings of Ur III still dominated Elam. Information and perhaps even cult practices from the south flowed back to early Sintashta societies. On the eastern frontier in Kazakhstan, where Petrovka was budding off from Sintashta, the lure of the south prompted a migration across more than a thousand kilometers of hostile desert. The establishment of the Petrovka metal-working colony at Tugai, probably around 1900 BCE, was the beginning of the second phase, marked by the actual migration of chariot-driving tribes from the north into Central Asia. Sarazm and the irrigation-fed Zaman-Baba villages were abandoned about when the Petrovka miners arrived at Tugai. The steppe tribes quickly appropriated the ore sources of the Zeravshan, and their horses and chariots might have made it impossible for the men of Sarazm to defend themselves.

...] from:

https://erenow.net/ancient/the-horse-the-wheel-and.../16.php